No bird gives birth to live young. Instead, birds prepare nests to cradle their eggs and their developing young. Caring first for the eggs and then for the young requires a major commitment of time and energy, often by both sexes. The associated risks also are great. The vulnerable eggs, nestlings, and attending parents tempt a host of predators. Additionally, activity at the nest, comings and goings to and from rest breaks, or feeding a mate on the nest draws attention to the nest and increases the risk of predation.

Most birds breed within a limited window of time that depends on the seasonality of the local environment and on aspects of that bird species natural history, such as its diet, predators, nest type, and habitat.

Resource availability and breeding time:

Most birds in temperate regions must breed within the resource-rich spring period driven by a seasonal flush in vegetation, the hatching of insects, and the oncoming summer warmth.

Seasonal temperature fluctuations become less dramatic towards the equator, and in many tropical habitats, it is seasonal variation in rainfall that drives annual cycles in resource availability.

Therefore, the timing of breeding is often less constrained for birds that breed in the tropics, where some species breed exclusively during a dry season, others find optimal conditions during the transition between dry and wet seasons, and a few can breed year‐round.

Insect season and feeding young ones:

The timing of food availability for their young is the factor that seems to have the greatest overall influence on when birds breed. Ideally, nestlings will hatch just when those food resources are most plentiful. However, birds often must lay eggs while food supplies are still rising, especially in environments with strong seasonal changes in resource availability. Since many species, particularly passerines feed primarily on insects for their nestlings, these avian parents often lay eggs just before peak insect abundance. In the most extremely seasonal locations towards the earth’s poles, the breeding season of avian insectivores may last only a month or so due to the correspondingly brief period of insect abundance in arctic habitats.

Bird species that feed their chicks on food other than insects often breed at different times than insectivores in the same avian community. For example, American Goldfinches of North America rely almost exclusively on thistle seeds to feed their young. This species, therefore, breeds in mid‐summer when thistle seeds ripen rather than earlier in the spring. Elsewhere, many honeyeater species in Australia breed when and where they can find the abundant blossoms of key Eucalyptus tree species. Likewise, Eleonora’s Falcons in the eastern Mediterranean lay eggs in late summer, ensuring that the peak food demands of their nestlings coincide with the parents’ prime hunting season during the fall land bird migration.

Breeding month prediction:

The more regular the seasonal changes, the easier it is for a potential breeding bird to predict them. In most environments, year‐to‐year fluctuations are minor enough that the breeding season falls within a predictable period each year. Most birds’ reproductive systems are primed to be active only during these months. The avian internal clock relies on changes in day length, or photoperiod, which cue a cascade of physiological preparations for breeding. Birds generally use photoperiods to establish their general breeding period but often rely on other cues to fine‐tune the initiation of breeding.

Nesting failure:

Successful nesting is the driving force of bird breeding behavior. The challenges, however, are many. The causes of nest failure include predation, starvation, desertion, hatching failure, and adverse weather. In general, nesting success increases in northern latitudes, in hole-nesting species, and large species with hardy young.

Predation causes by far the greatest number of annual nest losses in all habitats and on all continents. Predation on nests and their contents severely reduces breeding success: more chicks may leave the nest through the stomach of a predator than on their own.

This mega source of natural selection affects not only nest architecture and placement but also the evolution of life-history traits, such as clutch size. Nest predation also forces species to compete locally for limited safe nest sites, affecting which species can coexist.

How birds hide their nest:

Songbirds hide their smaller nests in diverse sites, including green plants overhanging water and the outer twigs of bushes and trees, or suspend them from vines. Domed nests that hide the contents from predators overhead came to characterize many of the smallest songbird species throughout the world. The woven nests of caciques and weavers dangle from crowded tall trees, often over water.

Nesting behaviors of birds:

The diverse nesting behaviors of birds correspond to their diverse solutions to the local challenges of reproduction. Most birds build isolated hidden nests. The nests of approximately 20 percent of all bird species remain unknown or poorly known to science.

At the other extreme are conspicuous, open-breeding colonies, some with millions of pairs. In Africa, from 2 million to 3 million pairs of the finchlike Red-billed Quelea also known as the red-billed weaver or red-billed dioch nest in less than 100 hectares of thornbush savanna.

On the Peruvian coast, black-and-white Guanay Cormorants pack together at densities of 12,000 nests per acre and attain colony sizes of 4 million to 5 million birds. The burrows of nocturnal auklets, petrels, and shearwaters riddle the hillsides of some oceanic islets.

Birds build nests to protect themselves, their eggs, and their young not only from predators but also from adverse weather. Structure and function are inseparable in nest architecture. Conspicuous nest features provide protection. Subtle features aid in the regulation of temperature and humidity.

Nest shape

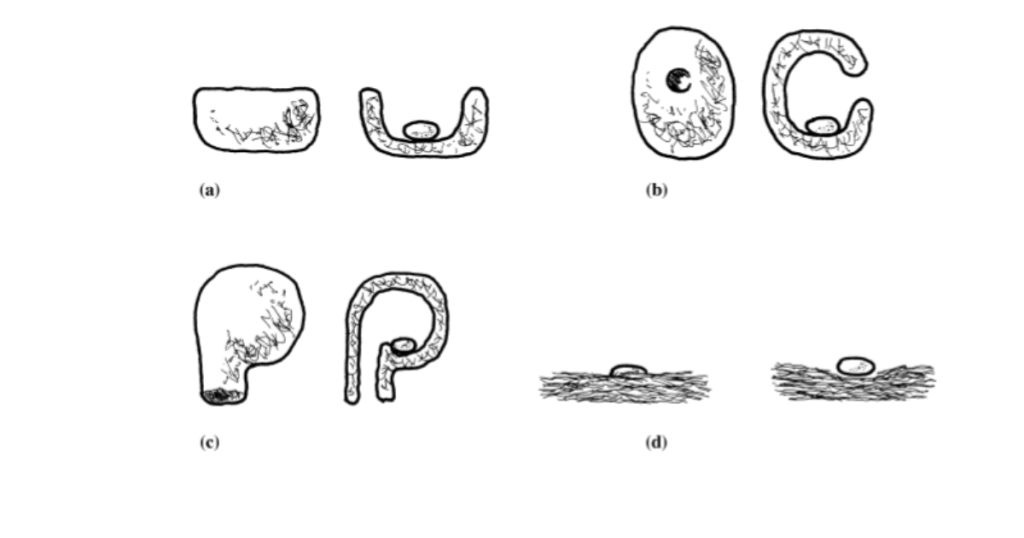

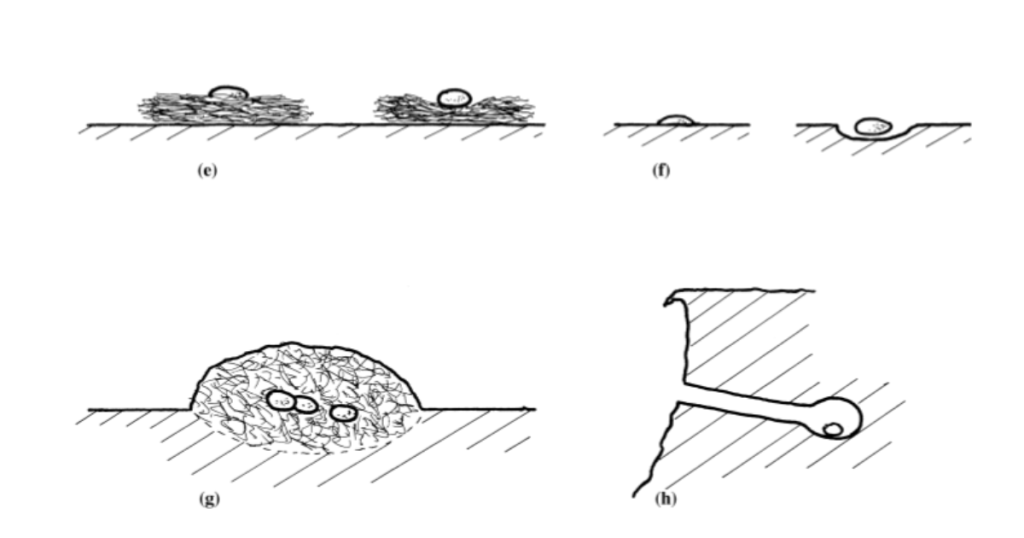

Eight mutually exclusive categories of nest shape are recognized: cup, dome, dome and tube, and plate, all of which are generally located above ground; bed, scrape, and mound, which are located on the ground. And burrow, which is located in the ground.

Cup is the shape of a nest with a distinct or prominent concavity to hold the eggs,

An above-ground nest with a shallow or indistinct cup is termed a plate. An example of the latter is the nest of the *woodpigeon (Columba palumbus).

A roofed nest is termed a dome unless it has an additional antechamber or entrance tube, categorized as a dome and tube.

Bed describes a flat or shallow cupped nest typical of some ground nesters;

Scrape a shallow depression in the ground with little or no gathered material;

Mound the nest structures of megapodes, where the eggs are buried within a constructed heap of material.

The category burrow is applied to a cavity excavated by the bird either in the ground or tree; where cavity nesters use ready-made sites, the nest shape is described in terms of the structure assembled within it.

Nest shape was recorded as one of eight possible categories: (a) cup; (b) dome; (c) dome and tube; (d) plate; (e) bed; (f) scrape; (g) mound; (h) burrow

Nest site

Eight mutually exclusive categories of nest sites are recognized:

Tree/bush, grass/reeds, ground, tree hole/cavity, ground hole/cavity, wall, ledge, and water. An additional category, no data, is used where no evidence of nest site is available, in the first instance from collection notes or published literature (Fig. 3.3).

Tree/bush includes any nest sited in branches of whatever size or height above ground.

Grass/reeds encompass nests like that of the *Eurasian reed warbler, supported on vertical stems,

while ground describes nests physically in contact with the ground or raised only a few centimeters above it on a cushion of vegetation.

Tree hole/cavity includes cavities in rotting branches or trunks, either excavated by the nester or adopted.

Ground hole/cavity similarly embraces sites in natural ground cavities (e.g., among rocks) and ground, excavated burrows used either by the diggers or secondhand.

Wall applies to a nest attached to natural cliffs or the walls of buildings where it receives little or no support from below.

Ledge, however, describes sites on cliffs or buildings where the nest does receive substantial support below it.

Finally, water is confined to nests made of materials that allow them to float.

Nest Materials and Architecture

Bird nests have genuine architecture. Bird nests are constructed from various natural materials by specific methods into highly functional designs that mediate the needs of the birds, their broods, and the conditions in their environment.

Other animals, including other reptiles, build nests, but birds do so in various forms, materials, and sites. Bird nests range from precarious constructions on bare branches to enormous communal apartments and simple scrapes on the ground to elaborate stick castles. In size, they range from the few sticks assembled by some doves to the gargantuan aeries of eagles. One Bald Eagle aerie weighed more than two tons when it finally fell in a storm after 30 years of annual use, repairs, and additions.

Nests may be casually constructed from ready-for-use pebbles and sticks or laboriously woven from natural fibers. Animal products, plant matter, and inorganic materials, including mud pellets, rocks, tin foil, and ribbons, are used in nest construction. Selected aromatic plant materials provide fumigants to repel parasites. The choice of nest materials can be extremely specific to species.

Thievery and Competition:

Birds go to extremes to get prime materials, which may be in short supply. Thievery is common, especially in a large seabird, heron, and penguin colonies. It is often much easier to steal than to collect fresh materials. Competition for small stones can be intense at Adelie Penguin colonies. Female Adelie Penguins have been observed soliciting copulations from extra-pair males in exchange for taking as many as ten pebbles from that male’s nest.

Saliva ingredient for nest soup:

Most swifts use their hardened saliva to glue their stick nests together. Palm swifts mix their saliva with fine plant fibers to create a felt-like material. Entirely self-sufficient are the cave-nesting Edible-nest Swiftlets of Southeast Asia. They make their nests entirely of their own (hardened) saliva. This sticky form of glycoprotein cements the nest together and attaches it to a cave wall. Because this unusual glycoprotein maintains its gluey consistency even when cooked, swiftlet nests are a critical ingredient of bird’s-nest soup. This gastronomic delicacy supports a substantial trade in harvested nests for sale to the Asian food industry.

Spiderwebs for construction:

Beyond basic construction materials, birds use spiderwebs for mooring or adhesion and feathers and hairs for the final lining. Feathers are often a major component of the nest, especially, the lining. The nests of Long-tailed Bushtits and Goldcrests in Europe may contain 2,000 or more feathers. Waterfowl pluck down from their breasts, and the Superb Lyrebird plucks down from its flanks to line the nest. Many birds pluck the hair, a premium nest-lining material, from livestock. Galápagos Mockingbirds snatch hair from the heads of surprised tourists.

Grass for construction

Grass is a widely used material, reflecting its extensive availability in a great range of habitats, but birds may distinguish different parts of the plant, selecting the part with properties suited to a particular function. Consequently, two further grass categories were required, grass stems and grass heads. The latter was generally of the head attached to a long stem but included heads that were compact or loose and somewhat varied. Creating four grass categories seems like making distinctions without significance, but this is not the case; for example, a grass leaf has the structure of a flexible ribbon, whereas a grass stem is designed as a stiff, hollow beam. This demands differences in building technique and suits them to rather different structures.

Nest fragrance

Nests of plant matter may contain twigs, grass, lichens, and leaves. Some birds add green vegetation that helps to combat disease and ectoparasite infestations. In general, hole nesters incorporate fresh, green vegetation more regularly into their nests than open nesters. Common Starlings select by the odor of certain plants, such as red dead nettle and yarrow, which contain volatile chemical compounds that inhibit the growth of bacteria and the hatching of the eggs of arthropod nest parasites.

Consequences of removing anti-bacterial plants:

The experimental removal of these green plant materials leads to a dramatic increase in blood-sucking mites, tiny parasites that can drain the blood volume of a starling chick.

Once the chick has hatched, Broad-winged Hawks bring fresh green branches of white cedar, ferns, and hardwood trees every day to line their platform nest.

Blue Tits on the island of Corsica also add fragrant plants to their nests. They select by odor fragments of as many as five herb species that Corsicans use to make aromatic house cleaners and herbal medicines. The birds also refresh the bouquet of odors, selectively replacing, using olfactory cues, herbs that wane or are removed.