Feathers, the most distinctive feature of avian anatomy, are an extraordinary evolutionary innovation.

Collectively referred to as plumage, feathers are the most complex structures to grow out of the skin of any vertebrate, and they provide a rich diversity of functions in the lives of birds. They provide:

- Insulation for controlling body temperature.

- Aerodynamic power for flight.

- Colors for communication and camouflage.

Modified feathers also perform secondary roles—in swimming, sound production, hearing, protection, cleanliness, water repellency, water transport, tactile sensation, and support.

Birds and Dinosaurs:

Dinosaurs are of constant fascination to humans all over the planet.

One hundred fifty million years ago, birds were giant animals roaming free across the planet until 65 million years ago, when that big asteroid hit, causing a massive extinction across our planet.

How did they survive the asteroid hit:

Obviously, our ancient mammalian ancestors survived, as were many other animals, mostly by burrowing into the ground or hiding in the water to escape the initial heat and then surviving on smaller prey during the ensuing years of cold. However, the big fellows like diplodocus would never have survived. They couldn’t seek shelter and needed far too much food.

How did tyrannosaurus become a bird?

As per new research published in Science, some dinosaurs did survive, the smaller ones. Scientists at the University of Adelaide analyzed the skeletal characteristics of 1,500 dinosaurs over 50 million years. Theropods, a carnivorous dinosaur family including tyrannosaurus, got smaller and smaller over that time.

They got smaller in 12 separate mutations, going from 163 kilos on average to the 0.8 kilos Archaeopteryx, the first bird.

How they evolved and adopted:

Because they kept getting smaller and ate meat rather than plant life, they survived the asteroid strike and ensuing extinction.

The meat-eaters survived because they didn’t require as large a body as plant eaters. Less body means less to take care of, which means survival!

Separate research, also published in Science, theorizes that All dinosaurs had feathers. Some were more primitive, like hairs or bristles, while others were soft and downy, like modern birds. They discovered this when they found a new dinosaur called Kulindadromeus zabaikalicus, which had feathers but couldn’t fly. This, combined with other evidence, is enough to make a theory but not a final determination.

Taken together, it’s pretty easy to see that modern birds are probably tiny dinosaurs, and the scientists were quoted in the Washington Post saying, “Without a doubt,” that is the case.

But why would these dinosaurs get smaller?

What would be the purpose?

Scientists say there would be a distinct advantage. Smaller carnivorous dinosaurs with feathers could climb trees, glide, and maybe fly, allowing them to hunt prey that differed from their larger carnivorous brethren, also helping them survive extinction. “They just knew how to innovate, evolutionarily speaking.”

If this is true, then instead of being extinct, there are 10,000 species of dinosaurs living and breathing on our planet today, even more than there are mammals or reptiles! Maybe you had some fried dinosaur for dinner last night or went out to fill the dinosaur feeder in your yard, or perhaps you have a pet dinosaur in a cage in your house.

Let’s come back to birds and feathers,

Feather Elements:

Feathers consist mainly of beta-keratin, a fibrous protein polymer that forms microscopic filaments with strong mechanical properties. Beta-keratins are unique to birds and other reptiles. Beta-keratins have similar mechanical properties to the alpha-keratins found in all vertebrates (including ourselves) and birds, but they are an entirely unrelated family of proteins with a very different molecular structures. Beta-keratins make up most of the hard structures of reptilian skin and the leg scales, claws, and beaks of birds. Feather keratins are a special class of beta-keratins characterized by a small deletion in their molecular sequence.

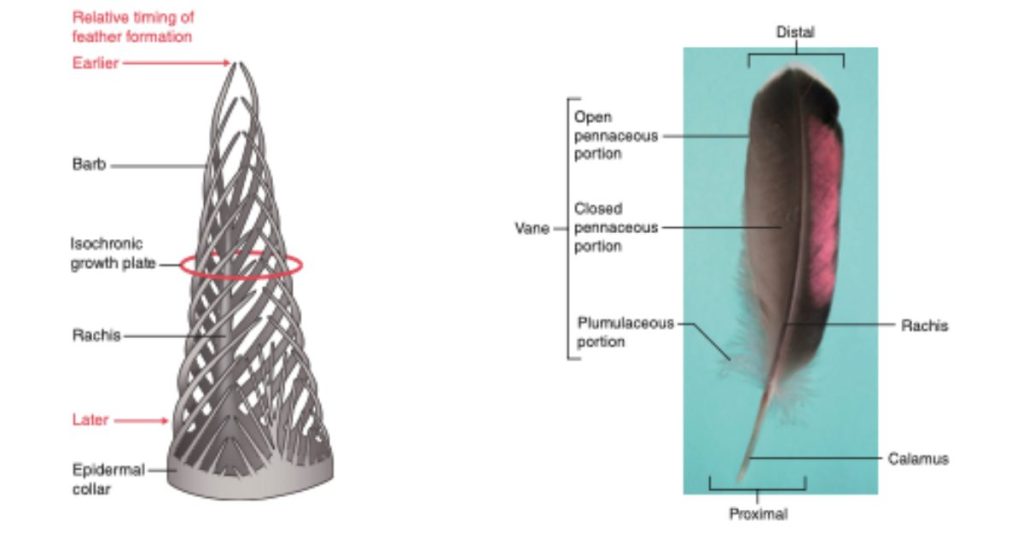

We begin by reviewing the structure of a typical body feather, called a contour feather.

Shaft: the stiff, central spine of a feather from which the vanes, if present, extend.

Vanes: the broad, usually flat, surfaces that extend from the shaft of contour and flight feathers; the vanes are formed by interlocking barbs.

Calamus: The shaft can be subdivided into two regions. The more medial (or close to the body) portion of the shaft is vane‐less and defines the calamus area.

Rachis: the portion of the feather shaft distal to the calamus; it is often relatively solid and supports the vanes when present.

Pennaceous describes that portion of the vane that is relatively flat and has a defined shape.

Plumulaceous describes that portion of the vane for which the loose, fluffy barbs are not structured into flat vanes.

Barbs: the regular, parallel fibers that extend from each side of the Rachis to form the feather vane.

Ramus: the shaft of a feather barb (from which barbules extend).

Barbules: Branchlets off the barbs of a feather that hook together with adjacent barbules.

Barbicels (or hooklets): Each barbule consists of a series of single cells fused end to end; the cells may be simple or may bear projections called barbicels, which may be elaborate and hooklike.

Keratin: a stiff protein that forms scales, claws, and feathers.

How feathers are formed:

Like hair, feathers are dead structures when mature. After fully grown, feathers cannot change color or form except through fading or abrasion. The first feathers of a bird develop on the embryo within the egg. Thereafter, feathers are replaced through regular, periodic molts throughout the bird’s life. Individual feathers may be replaced anytime if they are accidentally lost or damaged.

Feathers grow from specialized organs in the skin called follicles.

The developmental mechanism of feathers is unique. Feathers are branched like a tree, but they grow from their base-like hair. Like hair, the tip of the Feather is older than its base, and each barb is older than its connection to the Rachis. Thus, barbs do not grow from the Rachis. Rather, barbs grow and then fuse to the Rachis.

As the feather germ emerges from the skin, the epidermal cells produce beta-keratin.

You can just imagine how much energy is being spent at the bottom to create all these new cells. At the bottom of the Feather, all the cells are undifferentiated skin cells, but they quickly start to differentiate and form the overall shape of the Feather.

Once the Feather has formed that differentiated Feather shapes out of skin cells, the skin cells go through a process called cornification. Each of the skin cells will produce a keratin skeleton inside of themselves, and it makes them very, very strong. It’s made of protein. Once that skeleton is complete, they get rid of all its organelles and the nucleus, which means the cell is dead. All that’s left behind is that strong skeleton of protein.

image

This should be mentioned at this point that the delicate work is all happening outside the bird, right on the skin’s surface. So to protect the process from dirt and bacteria, the whole Feather is inside a protective cylinder also made of keratin. You can see these cylinders on birds sometimes. They look like little white lines. It’s a new feather under construction. These are called pin feathers because they look like pins or blood feathers because there is still some blood circulating as the cells finish their growth. Inside the tube, the Feather is organized.

Here is a cross-section of what is happening. The center is just supporting cells providing a frame for the feather cells to stay in place. You can also see the blood vessels here. On the outside is the protective waxy cylinder. The Feather, in red, has several barbs, and these little lines are barbules, the smallest parts of the Feather.

How do different shape feathers grow?

Using different cellular directions, the bird can form different feathers. This is a downy feather with long barbs barely connected at the end. But the bird can also print flight feathers, semiplume feathers, or bristles. It’s all the same process, just different instructions.

Feather and what part of the bird it’s from:

All feathers are made from the same protein, and they all grow out of feather follicles in the bird’s skin. The only difference is how the Feather is formed. There are seven distinct types of feathers. And if you learn all seven, you can tell which one you have just by looking at it. Let’s go through each of the seven types and see what makes each one different.

Flight feathers:

Flight feathers are all located on the wing, and they’re distinct. They’re big feathers that don’t have any gaps. If you flap them through the air, you’ll feel air resistance and notice that the central Rachis is off to one side, not right down the middle. And that’s the best way to know that you have a flight feather, you can even tell what side of the bird it’s from. Figure out which side is the top. The colors might be different, and the feathers almost always curve a little. And the bottom of the arch is the bottom of the Feather now. The smaller side goes towards the front of the bird. Turn your feathers, so the smaller side is forwards. Now you know which wing the Flight Feather came from.

Flight feathers have many links between the barbs, which is how they keep their shape and air from passing through the feathers. So these feathers are light and strong enough to push air and keep the bird up in the sky.

Tail feather

Tail feathers look a lot like flight feathers. They’re big and solid feathers that don’t let air pass through. But if you look at the central Rachis, you’ll notice that it’s more towards the center. Most birds have twelve tail feathers. The center feathers are even on both sides and get more asymmetrical as you move outwards. Tail feathers are used for steering in flight. But some tail feathers, like those of a pheasant, are used primarily for display.

Contour Feather

Contour feathers are the vast majority of feathers that you see. Contour feathers have a tightly linked top that blocks air and a fuzzy lower part that lets air pass through. They cover the bird’s body. The tops overlap to make a smooth layer of feathers that keep the bird waterproof and give it an aerodynamic shape. And these feathers are where a lot of birds have patterns and colors. The top of this Feather has lots of links holding the barbs together. That’s why it has a flat, smooth shape. The bottom of the Feather has way fewer links. So the Feather doesn’t hold a consistent shape.

Semiplume Feather

Semiplume feathers. Go one step further. They have a central Rachis. Usually right down the middle, but they have almost no links anywhere on the Feather, so the whole Feather is loose and fluffy. These feathers help make air pockets that hold warm air close to the body. The air pockets keep the bird warm, even when it’s freezing outside.

Down Feather

Down feathers are all about insulation. You’ll know you have a down feather because it is tiny and fluffy. Down feathers have that lower part that connects to the bird, and then they have almost no Rachis in the middle, just barbs. These feathers are all about insulation. This is what they use if you ever see some clothes that are insulated with down feathers. Those floating barbs trap pockets of air and keep the cold air off the birds and people.

Bristle Feather

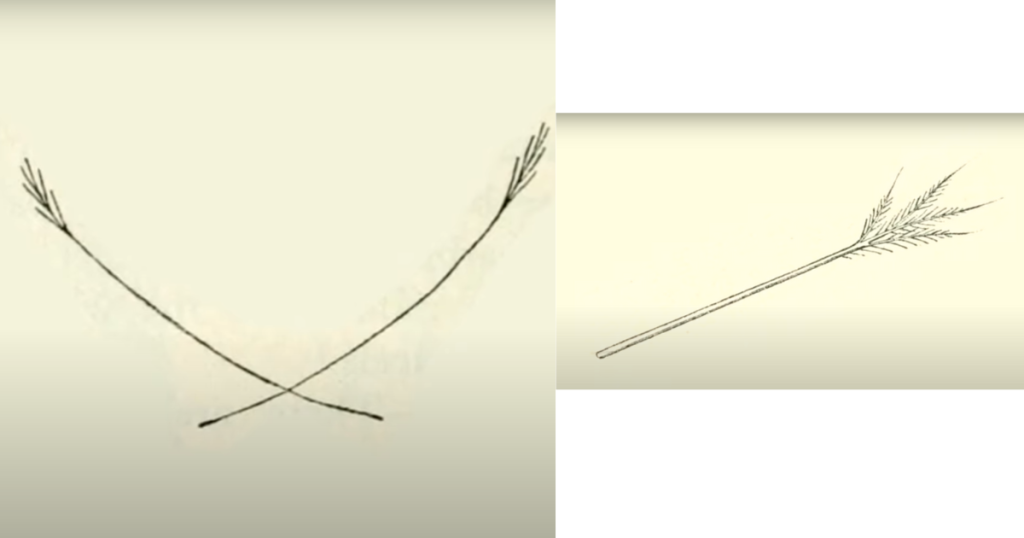

This type is hard to see on a bird, and good luck finding one on the ground. Bristle feathers are just the central Rachis with no barbs. It’s still a feather. It grows out of a feather follicle and looks like a whisker or hair. But birds don’t have any hair. It’s all feathers, and in this case, bristle feathers. A place you can find bristle feathers is around the nostrils of a macaw. These probably keep dirt and debris out of the bird’s nose, just like hairs would in mammals.

Filoplume

Filoplume feathers are hard to see on birds, but nearly every part of every bird species has at least one Filoplume Feather. They’re like a bristle with a tuft at the end. They’re short and sit between the other feathers. Nobody knows exactly what they do, but they seem to be used to sense feather position and if any feathers are missing.

This process is amazing and complex, but it happens all the time.

Bird feathers are replacing themselves regularly. Old ones fall out. New ones grow in. It’s why birds can have a covering that is so light and delicate.

To learn more about feather colors, click here,