Rain is a matter of survival for some birds. The extent to which heat loss can be minimized and increased heat production determine whether a particular bird can survive in cold climates.

Let’s find the answers to some important questions on

how birds survive cold temperatures,

how they stay dry,

how they decrease heat loss,

how they fly in the rain,

where they stay etc.

Where do birds go when it rains?

They take shelter in bushes and trees. Or in cities, they go under bridges and windowsills and roof overhangs.

The big exception to this hiding behavior is birds that already spend their time in the water. You can still find ducks, geese, and gulls acting normally in the rain.

But most birds try to wait in a sheltered spot to stay dry until it stops raining. But if the rain goes on long enough or the bird is hungry enough, they eventually leave their shelter to find food.

How does it stay warm despite the low temperatures?

Birds that live in cold environments must adapt physiologically. Yet, most birds do not show the major seasonal adjustments in insulation common in mammals, which often add hair and fat as winter approaches.

Birds facing temperatures below their thermal neutral zone have two other options:

- either increase heat production, usually through shivering of the large flight and leg muscle groups,

- by abandoning homeothermy, either for a period of time or in parts of their body.

How do various species of birds adapt to winter?

Small birds with relatively large surface areas for heat loss, like finches, chickadees, tits, and kinglets, must be able to increase their metabolic rate in the winter in response to cold. This is quite an amazing feat given that, at the same time, they also face shortened day lengths that limit their foraging time, long nights of low temperatures, and often less access to food due to snow cover or inclement weather. As a result, acclimatization may be necessary, particularly for species in high latitudes.

For example, many studies of birds such as European Goldfinches, Common Redpolls, Dark‐eyed Juncos, and Black-capped Chickadees have shown that they have a greater capacity to increase heat production in response to cold temperatures in the winter than they do in the summer.

In House Finches and House Sparrows, individuals in northern populations tend to have higher metabolic rates than those in southern populations.

We also know that some small high‐latitude residents like Great Tits and Common Redpolls will allow their core body temperature to drop slightly, but only when food is in short supply, thereby achieving significant energy savings.

In contrast, Willow Tits in the same habitat lower their body temperature on cold nights even when food is abundant.

Ways birds choose to decrease heat loss:

Birds decrease heat loss in the winter by choosing protected roosting sites such as dense foliage or tree cavities. Grouse and ptarmigan that roost in snow burrows are within their thermal neutral zone under the snow. In North America, Verdins build winter nests, which provide more insulation than summer nests, and there are reports of up to 16 Black‐tailed Gnatcatchers roosting together in winter Verdin nests.

Dangers staying in winter nest:

Presumably, most birds do not roost in winter nests, even in cold climates, because of the inherent danger of predation when they return each evening to a predictable and conspicuous location.

How do water birds survive cold?

Birds like ducks and gulls that must spend long periods standing in icy water use regional heterothermy, maintaining the temperature of their core body while allowing the temperature of their extremities to fall to near ambient temperatures. Because of their large surface area, low heat production, and poor insulation, appendages like webbed feet are very hard to keep warm; for a duck or gull standing on ice, keeping the entire leg and foot warm would entail a tremendous energy cost. Instead, these birds allow the foot to approach freezing temperatures, thus decreasing the temperature gradient for heat loss to the environment.

Process of dealing with heat loss:

Blood must still be supplied to the foot, however, and the birds use a countercurrent heat exchange system to reduce heat loss. The heat from the warm blood in arteries supplying the foot and leg is transferred to the adjacent veins grouped around the artery that return cool blood from the foot. This countercurrent heat exchange system can efficiently maintain heat in the core and minimize heat loss. As a result, increases in blood flow periodically maintain little heat in the foot to prevent it from freezing. Bird’s feet do not consist of much muscle or nerve tissue, unlike humans so they can withstand low temperatures without damage.

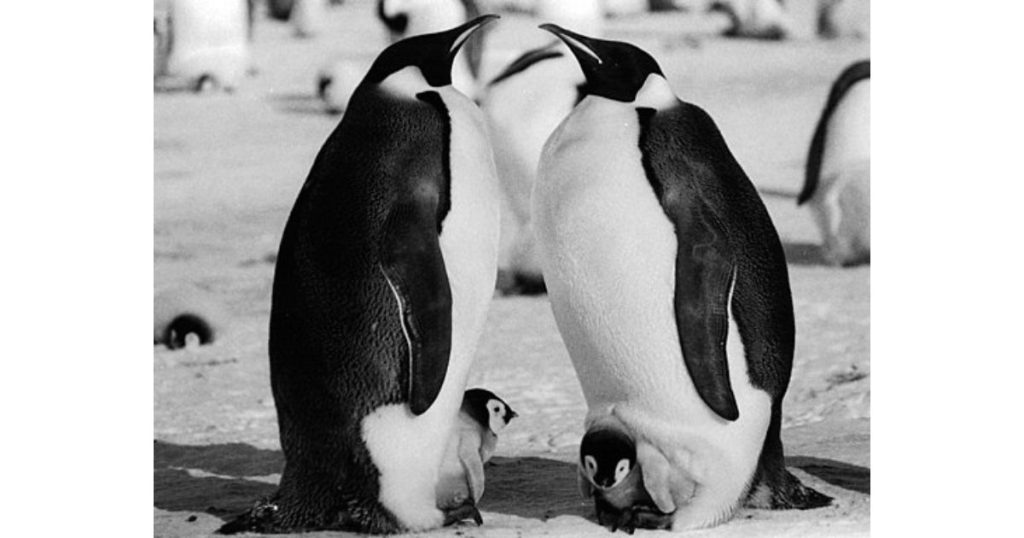

The fascinating story of Male Emperor Penguins incubating eggs during winter:

Emperor Penguins are famously known for surviving cold exposure. Male Emperor Penguins must incubate their single egg in the midst of the antarctic winter at temperatures as low as –30 to –40 °C. During an extended incubation bout of over two months, the male does not eat while he waits for his mate’s return at about the time the egg hatches. Despite their large size and thick insulation, the energy male penguins would need to maintain homeothermy under these conditions, plus the energy needed to walk back to the ocean where food can be obtained greater than could be generated even if they used up their entire fat stores.

How do male birds survive this?

It appears that the only way these males can survive this ordeal is to huddle closely together in large groups. Birds in the center of the huddle are protected from heat loss by their closely packed neighbors, thereby conserving energy, until they are forced to take their turn on the perimeter of the huddle, where heat loss and metabolic expenditures are much greater.

Heterothermy and birds recovery:

Some birds regularly abandon homeothermy altogether, allowing their core body temperature to drop while they undergo bouts of torpor, a strategy known technically as temporal heterothermy. Shallow torpor, sometimes called nocturnal hypothermia, is a relatively modest decline in body temperature, usually to no lower than 30 °C. Shallow torpor has been observed in numerous birds, including vultures, anis, doves, and quail, and several passerines, including some sunbirds and manakins. Deep torpor (decreases in body temperature to levels at which the bird cannot respond to external stimuli) has been observed in hummingbirds, some poorwills and nightjars, mousebirds, and some swifts. In most cases, these birds appear to be reluctant heterotherms, only resorting to torpor when facing an energy crisis in inclement weather. This is understandable because a torpid bird has very poor escape reflexes and is, therefore, highly vulnerable to predators.

Small bird’s torpor for winter:

On the other hand, some hummingbirds in cold regions of the high Andes appear to use bouts of torpor every night, which may also be true of other small nectar‐feeding species. Deep torpor is a strategy that small birds most easily employ because it simply takes too long for a large bird to cool down and rewarm on a daily basis.

Common Poorwill hibernation during winter:

One species, the Common Poorwill of North America, is the only bird known to use multi-day bouts of torpor, interrupted by brief bouts at normal body temperature, much like hibernation in mammals. Torpor is not completely abandoning thermoregulation but is still a physiologically controlled state since birds can spontaneously arouse (rewarm) to the normal body temperature. In addition, during torpor, a bird’s heat production often varies with changes in ambient temperature, just at a lower set point than normal.

Why torpor is important

The energy savings from abandoning homeothermy at cold temperatures are obvious. It might seem less obvious why several tropical species also employ temporal heterothermy. Any drop in body temperature, however, will produce energy savings. These savings could be important for small birds like manakins that eat low‐energy fruits. Likewise, the shallow torpor that desert roadrunners use is probably important in the winter when reptiles and insects they typically prey on decrease dramatically in abundance. Given the common occurrence of some level of hypothermia in so many species of birds, it is probably an important strategy that contributes to the ability of birds to occupy a wide array of habitats and climates.

How do birds stay dry?

That has a much more interesting and surprising answer. Birds have a couple of ways to resist water. Most birds have an oil-producing gland on their back, just above their tails.

It looks like a little bump. Birds can run their beaks on the bump to get some oil and then spread it across every single feather on their body. When birds are preening, this is what they are doing. Get some oil, and spread it on the feathers. They coat themselves with a water-resistant layer of oil. So if they need to hop out in the rain, they can stay dry for a little bit of time.

Those birds that live in water usually have strongly developed oil-producing glands. So their feathers are able to resist water for swimming, and rain falls off them like, well, like water off a duck’s back.

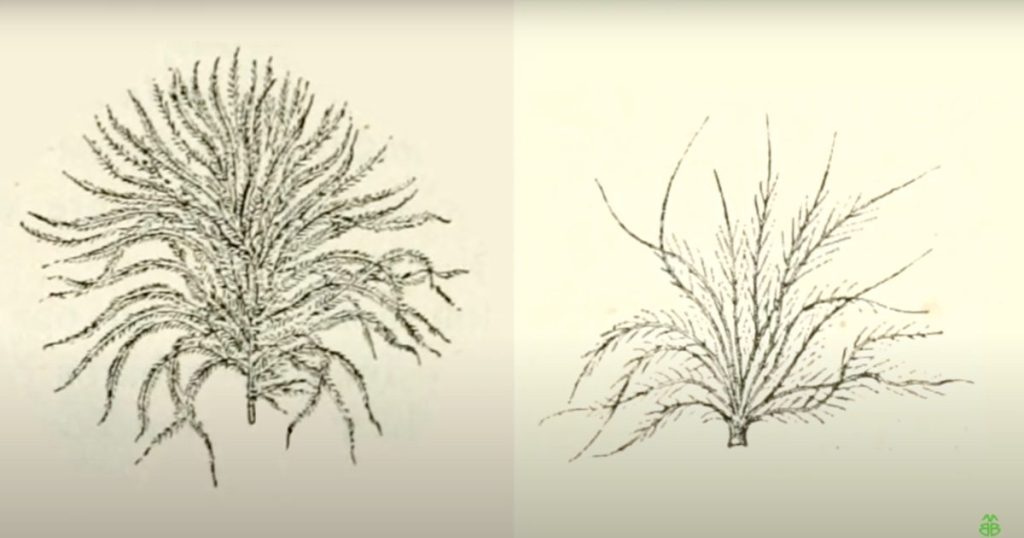

There is an alternate way that birds have found to keep their feathers dry, called Powder Down. Deep under the outer layer of feathers is soft, fluffy down. It has these long fluffs. Almost every bird has down feathers. But some birds have Powder Down feathers.

These are down feathers that have more branching and never, never stop growing.

The first one is a down feather. And the second one is a powder-down feather.

You can see the long barbules. Those barbules break off into little pieces of dust and get all over and in between the other feathers. Then, when it rains, it beads up and bounces off this feather dust.

Birds that have powder down include parrots like cockatoos, herons, tinamous, and bustards. I am still looking for whether there is a common factor between which birds having powder down instead of an oil gland. If you know, please let me know in the comments.

Birds will indeed choose to bathe in a puddle, or sometimes out in the rain, to help clean their feathers. But when it rains, most birds will choose to take cover or rely on their oil or powder to stay dry.

Do birds enjoy the rain?

Some birds don’t mind the rain, but a 2010 study found that research conducted on birds of coast Rican forest taking their blood samples found that stress hormones are high in birds during rain. After all, many animals feel stressed out during storms.

Can birds fly in the rain?

They can, but they don’t prefer it if they are in need to get food, they will fly and search for food, but most of them prefer not to. Rain is no fun for lots of birds. They are covered in a delicate layer of feathers that work best when dry. A wet bird loses heat more quickly and cannot fly very well. So birds do not fly, and most find a spot to stay dry during rain.

How do they cope with heavy rainfall or storms?

One of the most important things about birds and storms is that they’re very good at surviving them. They sense a storm coming, and the first thing they do is find a nice big thick bush, a big thick hedge, and they dive right down into it, and they can hang out there for some time because they have fabulous physiological adaptations that allow them to cope with this kind of bad weather.

They have wonderful feathers, which sort of look like this

image

There’s space between the feathers. The air gets trapped in there. Even though the wind is coming, it can’t push that air out from the feathers. It’s the trapping of that air that provides the insulation.

The other major adaptation they have is special things in their feet called a countercurrent exchange. And the idea is that we have an artery coming down the leg, and then the vein coming back up, but we will lose heat outside the foot and the leg.

But the birds have them very close. So, as this cold blood is coming back up the foot, all the heat from the artery moves over into the vein, and it doesn’t lose very much heat through its feet. So even though they have no feathers on their legs and these little bare stick legs running around in the snow, they’re perfectly fine.

Can they get sick by being exposed to heavy rainfall?

Rain poses two major possible health risks to birds,

- Hypothermia

- Starvation

Hypothermia

As we discussed earlier, birds stay warm during rain by trapping tiny pockets of air. If those pockets are filled by water due to heavy rain, it causes major risk.

Starvation:

If the rain is a week-long downpour, it is not something birds can wait for, especially if you are a small bird without much energy stored. You have to get wet in such cases to find food.

Why do birds find it difficult during rain?

With most rainstorms, there will be a drop in air pressure, which makes the air less dense, and birds find it very difficult to fly in such conditions as it requires a lot of energy, so most birds will be sitting on tree branches or power lines during that time.

when it rains, most birds will choose to take cover, or if they have to go out, to rely on their oil or powder to stay dry.

Thanks for taking the time to learn about birds.