In preparation for hatching, bird embryos produce an egg tooth, a short, pointed structure found on the tip of the upper beak and occasionally on the lower beak as well.

While in the egg, the avian embryo generally looks to be in a “fetal position,” with its head bent forward to its belly. When it is ready to hatch, the fully developed embryo pulls its neck up and back (often by using muscles developed particularly for this task), rubbing the egg tooth against the shell’s inner wall, which has already been weakened in the development stages of the embryo by absorption of calcium.

Process and preparation for hatching

Embryos of most bird species turn inside the egg repeating this motion many times. Eventually, the chick manages to create a little hole in the eggshell, at which point the egg is pipped. Soon after, the chick begins to puncture the shell with a series of holes sometimes those were connected, and sometimes not they nearly encircle the sharp end of the egg. Once the shell is weakened enough, the chick pushes off the end, away from the egg membranes. This emergence requires a great deal of exertion, and once they hatch most hatchlings lie quite still. Once dry, most nestlings weigh about one‐third less than the whole egg from which they started. A few days after they have fully hatched, the egg tooth sloughs off or is reabsorbed.

The duration of time between pipping and hatching varies among species. Many passerines will complete the process in just a few hours, but some larger birds may require as long as 4 days. In many precocial species, siblings coordinate the synchrony of their hatching precisely by vocalizing to one another from inside their eggs. Once each soon‐to‐be hatching breaks the membrane of the shell the air cell in the blunt end of its egg, begins with peeps or rapid clicks produced several times per second, usually beginning a day or two before hatching until the time of hatching.

Development Categories of Hatchlings

Ornithologists recognise six development categories of hatchlings:

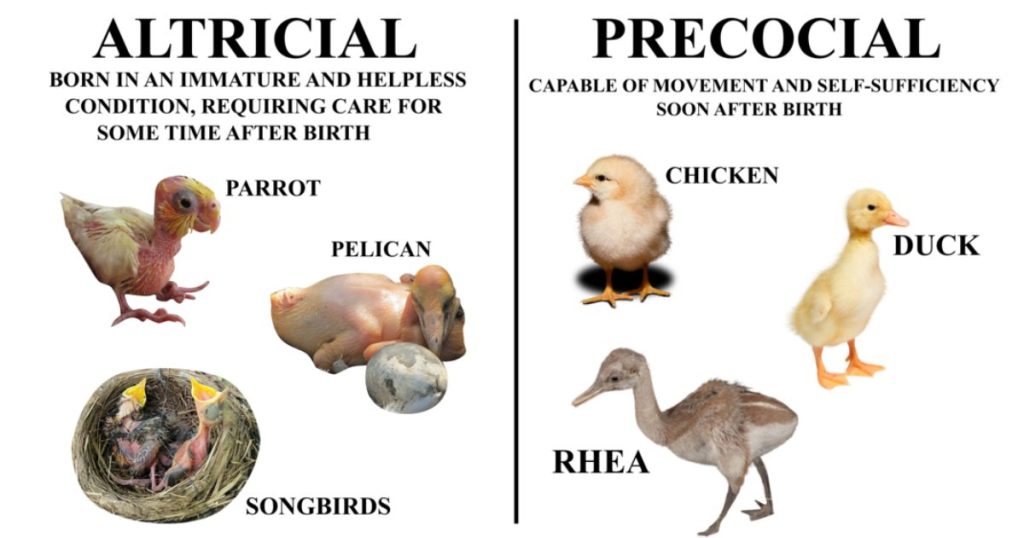

We here learn about Altricial and Precocial development in detail

Altricial and Precocial young

Newly hatched birds vary widely in their eagerness for life outside the egg.

Altricial chicks hatch naked or very scantily feathered, with no ability to generate enough heat for thermoregulation, and are completely dependent on their parents for food.

In contrast, precocial chicks are already well feathered while hatching, with substantial powers of thermoregulation and locomotion, and a considerable capacity of independence from their parents for feeding.

Appearance

The mouth of a newly hatched

No one will describe a young altricial bird as attractive. A newly hatched altricial nestling appears to be all head and abdomen, with two large eyes bulging against closed lids. Soon after hatching, it opens its mouth by lifting its head on its wobbly neck. Swollen gape flanges, with nerve endings, extend from the corners on both sides of the mouth and taper toward the tip of the bill; if you touch one of these flanges and the nestling’s mouth is likely to open like a mechanical toy. The colors in the mouth are often bright and contrasting, changing it into a target into which the parent birds place food. The flanges are generally white or vivid yellow; the lining of the mouth is often a vibrant orange, red, or yellow. In nestlings that are raised in cavity nests, the colors around the mouth will be even more intense, probably to help the parents find the chick’s mouth for feeding in low-light conditions.

Skin

An altricial nestling’s skin, which appears mostly to be pink from the muscles and blood vessels under it, and very thin and oily in appearance. The internal organs and an empty yolk sac, resorbed back into the embryo as it developed, visible through the skin of the distended abdomen. If the nestling hatches with any down, it will be most abundant on the top of the head and the back. The length and color of the down vary by species and may or may not follow the outline of the actual feather tracts soon to emerge. The first real feathers soon push out the down, although a chick usually retains wisps of the natal down on the tips of its juvenal feathers. The juvenal feathers begin to develop beneath the skin, first visible as small bumps on the skin and displaying as dark bands before they erupt into the pin feathers which will emerge throughout the chick’s development cycle.

In most altricial chicks, pin feathers occur first in the feather tracts of the head, wings, and back, and later on the underparts. For most birds, the wing feathers grow until full powers of flight are achieved at or after fledging. Because precocial embryos spend more time developing in their eggs than altricial species, precocial chicks are seen much more developed at hatching.

Perhaps the most familiar young bird is that of a newly hatched chicken, which well typifies precocial young. The chick’s downy which covers, wet from embryonic fluids, dry within 2 or 3 hours, taking a fluffy appearance that makes the chicks of precocial species so endearing. The sensory and motor capabilities of a newly hatched chicken, even after being in the egg for about 22 days, are almost as well developed as an altricial chick that has spent 12 days inside the egg and after hatching 10 days in the nest. As soon as they hatch from the egg, precocial hatchlings, with their eyes already wide open, react immediately to external stimuli, are remarkably adroit in maintaining and walking their balance, and eagerly begin exploring their environment and pecking at unfamiliar objects. This early neuromotor sophistication is the most rewarded hallmark of precocial chicks.

At hatching, the precocial chick’s abdomen still retains up to one‐third of the contents of the yolk sac, and its digestive tract is fully functional. The egg tooth is noticeable, flanges are either not present or reduced along the margin of the bill, and the color of the mouth lining will be plain similar to the adults because most precocial young feed themselves and thus they have no need to send begging signals to their parents. Precocial chicks generally have large legs and feet along with well-developed muscles for walking and heat-producing for thermoregulation. The most precocial of all birds, the megapodes, are the only birds whose embryos break out of their shells using their extremely large and powerful feet instead of using an egg tooth (“pod” is a root word meaning “foot”). Megapode chicks also receive no parental care. These chicks simply walk off into the surrounding forest as soon as they emerge from their incubation mounds, and even their wings are fully feathered at hatching, allowing them to flutter away from all threats they encounter outside the mound.

Temperature regulation

A newly hatched altricial nestling is incapable of regulating its body temperature. By brooding, the parents help to keep the nestling’s body temperature high, near the levels at which growth and digestive enzymes work best. As the nestling grows, its volume-to-surface area ratio becomes more favorable for heat retention, and it starts to grow its insulating coat of downy and juvenal feathers. Eventually, the nestling does the process of converting the food brought by its parents into energy and uses that energy for thermoregulation.

In contrast, precocial chicks hatch with one of nature’s best insulating materials a thick covering of down. Precocial chicks typically are larger than the average altricial nestling; thus, with a more favorable ratio in surface area to volume, precocial chicks tend to lose relatively less heat from their bodies. They can partially control their body temperature while hatching (well before altricial young can do so), although most still require some brooding. But after hatching, their temperature control develops much more slowly than in altricial nestlings; until about 4 weeks of age, some precocial chicks do not attain full temperature control. The feather coat development of each precocial species follows a pattern suited to its environment.

Some species and their temperature control techniques

Upland species, such as shorebirds and grouse, generally are more vulnerable to upward radiative heat loss, so they soon develop feathers on their back and upper surfaces. Aquatic species, such as loons, waterfowls, and grebes, first develop long, thick feathers on their body’s undersurface to help insulate the chicks when they are floating on cold water. After an initial lag of a day or two to allow the digestive system to prepare, altricial nestlings develop explosively, often doubling several times in mass during the first 10 days after hatching.

For example, the chick of an American Crow weighs only 15 grams while hatching, but after 18 days of growth, it will be increased by over 300 grams a 20‐fold increase.

Weight management – Obesity for a Purpose

In some altricial species, the nestlings put on so much weight in development that they temporarily weigh more than their parents. This extra energy may help to nourish young birds throughout the challenging period when the chicks must learn to forage on their own. In other altricial species, the fat stores however mostly depleted by the time the young leave the nest. Good examples of this weight recession can be seen among seabirds. The chicks of the Gray‐headed Albatross on South Georgia Island in the Southern Ocean, temporarily weigh up to 30% more than adults before they lose weight before fledging. In albatrosses, this phenomenon is considered to ensure adequate resources for chicks during the crucial development period of feather growth preceding flight.

Most precocial young, especially those that feed themselves, are somewhat inept at acquiring and ingesting food instantly after they hatch. For their first few days after hatching, chicks sustain themselves primarily on the large amount of egg yolk stored in their abdomens. They may lose weight during the transitional phase, but once they start to feed themselves efficiently, they gain weight in a way similar to that of altricial birds.

Metabolic rate

As chicks grow, their metabolic rates also increase. Although overall patterns of weight gain are similar in both precocial and altricial birds, their metabolic rates grow in strikingly different ways.

The increase in the metabolic rate of precocial species can be measured in two distinct phases:

An initial rapid phase shifts quite abruptly into a slower phase about halfway through development.

In contrast, the metabolic rate of altricial chicks increases relatively continuously as they develop.

Sensory and motor development

An altricial nestling’s sensory and motor abilities develop along with the body as it grows. At hatching, it is all but weak, able to stay upright only by leaning against the nest. However, it gapes, swallows, digests, and defecates the four behaviors which are crucial to obtain and converting food into a rapidly developing young bird. With most of its energy going into growth, altricial nestlings need to sleep, which they alternate with feeding. Most altricial chicks cannot even produce begging calls during their first day or so, but these calls will soon develop and become louder and more persistent as the nestling grows. At about one‐fourth of the way through the nestling development stage, their eyes open, allowing them to gape at visual stimuli (the parent, or even forceps holding food). Then nestlings begin to grab objects with their feet, although their balance is still poor. When defecating, the nestling raises its posterior and moves from side to side, thus making it easy for the parents to retrieve the fecal sac; many species will back up to the edge of the nest. A few days after their eyes were open, most altricial nestlings develop a crouching response to strange visitors to the nest, and in many species, they produce the same reaction to the alarm of their parents. By the time most of their feathers have emerged, their begging behavior seems to become quite aggressive. As the feathers continue to extend from their shafts, the nestlings begin their first preening activity, and they often begin stretching their wings up, back, and to the side.

Precocial chicks, although further ahead in their sensory and motor development at hatching, still need time to adjust to their new environment outside of the egg. Even megapode chicks pause underground after hatching, often resting for more than a day before they begin their rise up through the layers of mound material above them. For example, the chicks of a well-studied megapode, the Australian Brush‐Turkey, are born with their eyes closed and for several hours seen unable to raise their heads. In captivity, once the head is raised, chicks quickly begin to preen, making the plumage clean and dry and also removing feather sheaths. After 10 hours, chicks start to respond to light stimuli with open eyes. In the wild, brush turkeys begin digging the surface after this initial period of rest, and they develop as they proceed upwards. Along the way, the chicks also develop the ability to feed themselves, pecking at soil invertebrates they find along their paths. Within 24 hours, these brush‐turkey chicks will attain thermoregulatory abilities. As digging continues, the young brush turkeys become more and more efficient, in covering greater distances in shorter amounts of time until eventually, they emerge ready for life on their own.

Thus some of the development strategies of birds and the process involved.