Nests vary wonderfully in their composition and design.

Classified primarily by its shape each nest can be classified in many different ways, we will discuss below,

Ground nest

In several species, nesting involves only site selection but no further nesting construction activity.

Murres lay single eggs directly on rock ledges exposed, and New World vultures and condors lay their eggs on the floors of shallow caves. White Terns of tropical seas lay their single egg on bare branches, like the potoos of the neotropics.

The absence of a nest may be an advantage to these species for different reasons:

- They don’t need to waste the time and effort required for nest building, exposed eggs can be less conspicuous to predators, and also problems caused by ectoparasites may be less when chicks are not restricted to the same soiled spot.

Male Emperor Penguins build no nest, and instead, they have evolved an incubation pouch that is created by a loose bulge of skin above the feet; right after a female lays her seasonal single egg, she passes it onto her mate for safekeeping while she leaves to feed in the distant ocean for long period.

All brood parasites also come under the “nestless” category, as they are known to lay their eggs in nests built by other birds.

Scrape nest

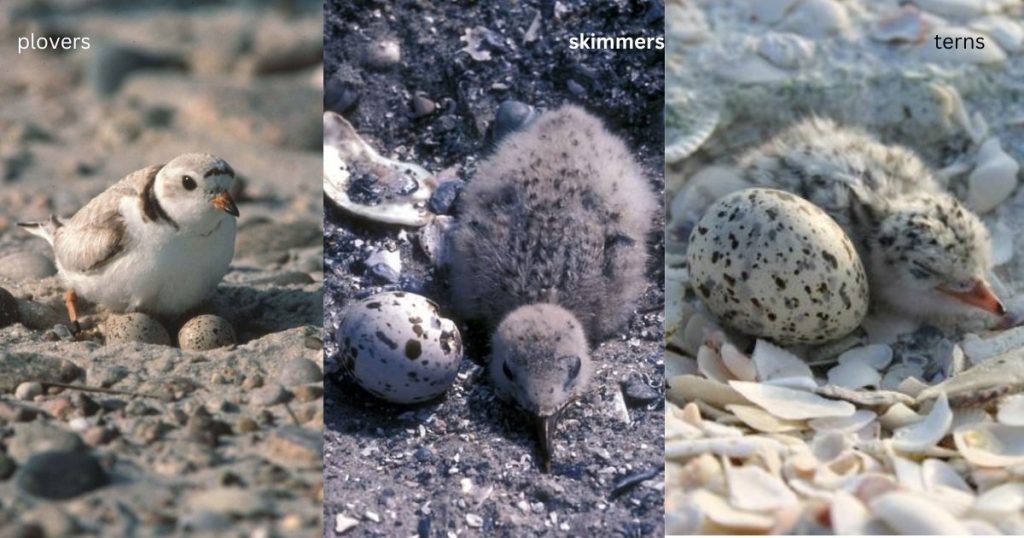

Some species’ nests consist of a simple scrape, in which birds form loose gravel or sand on the ground to create a slight depression for the eggs.

This can be seen in, many plovers, skimmers, and terns nest in a very shallow scrape, possibly lined with a few flat pebbles or nothing at all. If the substrate at their nesting site is too hard some scrape-nest species do not even create a depression at all, but they may still arrange flat pebbles and twigs to build a very rudimentary nest.

Platform nests

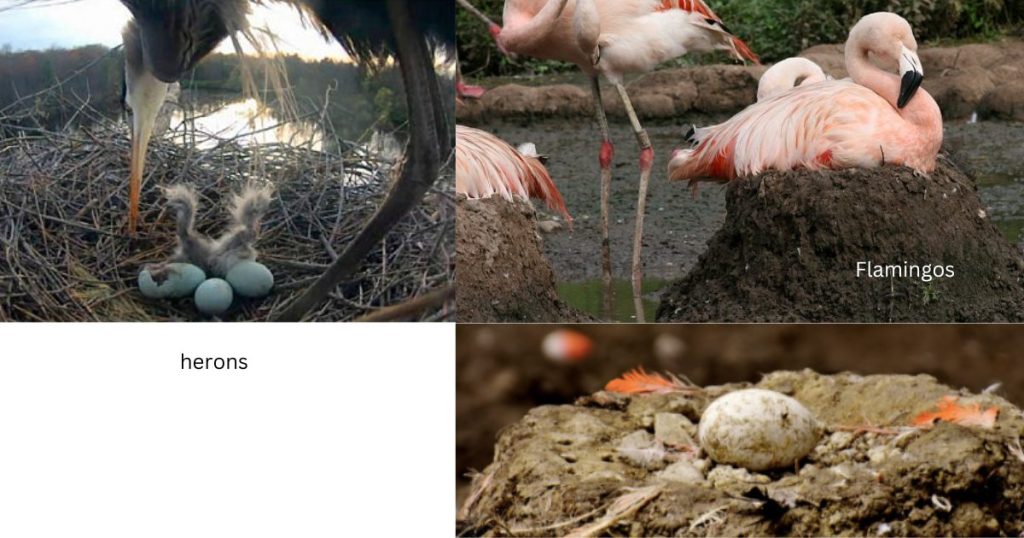

Platform nests consist of a mound with a shallow depression on its top. Different birds build platforms on the ground, within trees or shrubs, or even floating in the water. Platform nests tend to vary tremendously in complexity, from the flimsy nest consisting of twigs thrown together by most doves to enormous structures sometimes having thousands of large sticks built by storks or other large birds of prey like eagles and Ospreys.

Birds build platform nests anywhere they find strong support. Many herons, raptors, storks, and cormorants build platform nests in trees but also use the same types of sticks to nest on the ground if no trees are available. Oilbirds build platform nests inside the caves of South America. Flamingos build short pedestals of mud and terns, and some grebes, build floating rafts of marine vegetation to support their shallow nests.

A variant of the platform nest

The Horned Coot of South America builds an interesting variant of this platform nest: By occupying high Andean lakes with limited aquatic vegetation, these birds pile stones, and build a shallow nest of vegetation upon the stones at the water’s surface. The accumulation of stones built by several pairs over a few years can reach up to 4 meters in diameter and 1 meter high, weighing up to a metric ton.

Cup nest

The majority of birds build cup nests, structures with depressions on their top that are at least half as deep as they are wide.

Birds place their cup nests in a wide variety of sites:

- on the ground,

- beneath waterfalls,

- in trees,

- and within nest cavities of all kinds.

Cup nests come in a diverse array of materials and sizes, although they are most commonly made of mud or small twigs and dried grass.

Crows and ravens construct the largest cup nests; hummingbirds build the smallest, often by securing soft fibers and lichens from seeds with carefully collected spider webs. As outlined below, cup nests are categorized based on the nature of their support.

Statant cups:

Simple, hard surfaces on the ground, a cliff’s niche, or, most commonly, tree branches that support “statant cups,” structures supported primarily from below. Frequently, it’s just gravity that holds the nest in place. Bobolinks of the New World build their statant cups directly on the ground. Horned Larks do the same, with a slight twist: to keep their eggs slightly below the ground surface and to avoid foot traffic from large mammals, Horned Larks usually build their statant cups within large hollows of a hardened horse or cow hoofprints. Most of the nests built in trees and shrubs are also statant cups, ranging from the piles of grass and twigs built by songbirds to the heavy mud nests built by the White‐winged Choughs, Magpie‐larks, and Apostlebirds of Australia.

Pensile cups

“Pensile cups” hang by their rims, which are usually securely attached to delicate branch tips or reedy vegetation in wetlands. New World blackbirds, vireos, and many songbirds in Asia and Australia build pensile cups. The lack of sturdy structures and the nest’s belly hanging unsupported surrounding pensile cups often minimize predator access from below. Pensile nests with deeper centers are known as “pendulous cups.” These nests are usually woven from plant strips or fibers, birds usually enter from the top of such nests.

pendulous cups

Pendulous cups are characteristic of some caciques and New World orioles oropendolas, as well as some Old World weaver species.

Usually made primarily of mud and/or saliva, “adherent cups” attach securely even to vertical surfaces. Barn Swallows, which breed all around the northern hemisphere, build adherent cups by mixing mud with straw. As their former common name “Edible‐nest Swiftlet” suggests, the nests are also used as the main ingredient in an Asian delicacy called “bird’s‐nest soup.”

Bird’s‐nest harvest

People have harvested these nests for a long time in vast caves, risk of climbing rickety skyscraper-like scaffolds of bamboo to reach them. Recently, harvesters have rather constructed artificial caves for these birds where structures resembling human houses, with the open upper floor to the air and also the comings and goings of swiftlets. A swiftlet pair will usually hurriedly build another nest if the first is removed, but these alternate nests often contain bits of vegetation (along with saliva) but these are much less desirable as human food. Some bird species, mainly those that nest on the bare ground tend to build domed nests, amid vegetative cover. The woven dome, combined with the woven cup, hides the eggs or nestlings.

Globular nests

Globular nests are completely enclosed except for a small side entrance. Built-in trees or shrubs, these nests are characteristic of most wrens. For example, Cactus Wrens of North America build grassy spheres, oftentimes within the arms of a cholla cactus. In the same desert habitats, Verdins build small globe nests with spiny twigs, including the spines to the outside for added protection. Black‐billed and Eurasian Magpies build enormous globular nests of thorny twigs, sometimes inserting strands of barbed wire. Some New World flycatchers and Broadbills in Asia and South American ovenbirds deter predators by constructing their globular nests at the ends of long tendrils or vines. Southern Penduline Tits of Africa to foil predators build pendent globular nests with a false entrance. A prominent hole on the side of the nest is a fake entrance that leads to a dead‐end chamber; the true entrance is a hidden slit in the roof of the false entrance also acts like a door that closes behind the parent as it enters and exits the nest chamber.

Retort nest

A retort nest is a globular nest with added entrance tunnel. These nests are common among many African weavers, mud‐nesting swallows, and some swifts. The lengths of these tunnels can range from a few centimeters to more than one meter. Retort nests built with mud, with very thick‐walled tunnels, makes it very difficult for all predators except access to snakes.

Mound nests

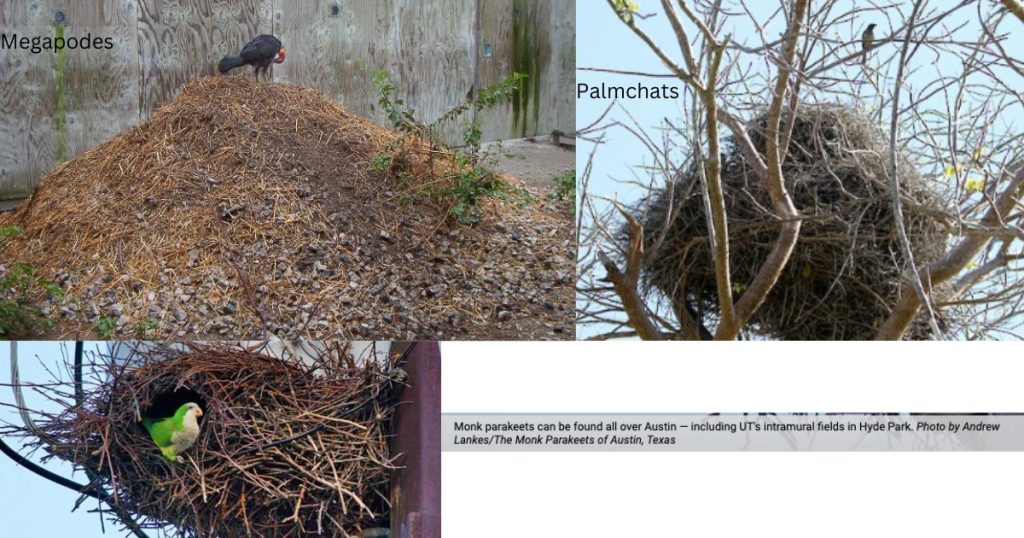

A few species build mound nests, which commonly consist of large piles of nest material in large trees or on the ground. Megapodes are the most famous mound nesters and the only birds that use the nest itself, as the source of heat for developing embryos.

Only a few passerine species are known to create true mounds: Several species of African social weavers and Palmchats on the island of Hispaniola build colonial mound nests resembling big, suspended haystacks in palms or trees. Monk Parakeets use sticks in their native Patagonia to build colonial mound nests. The odd, heron‐like Hamerkop of Africa builds an enormous mound nest in a large tree that ranges more than 2 meters high and wide. Hamerkop nests may include up to 8000 sticks and weigh up to several hundred kilograms. connected to the outside by a mud‐lined tunnel, the nest chamber lies in the center of the mound.

Cavity nests

A tree hole is one the most familiar sort of cavity nests. All woodpeckers are capable of excavating their nest cavities, even in healthy tree trunks sometimes, thanks to a host of adaptations. Although woodpeckers are experts at creating nest cavities in trees, many species of parrots, nuthatches, barbets, toucans, and tits are even capable of modifying preexisting holes according to their needs. As mentioned earlier, some tropical birds dig nest cavities in arboreal termite nests.

Burrow nests

Burrow nests are a kind of nest where cavities in the ground seem to be longer than they are deep. Numerous species found in different avian families excavate burrows in moist sand or sandy soil. In contrast to the physical characteristics required to burrow in wood, soil excavators won’t usually have specialized adaptations to perform this task. Examples from the temperate zone include the Bank Swallow and the Common Kingfisher both loosen the soil with their bills and with their weak feet they clear a tunnel.

Cavity adopters

Cavity adopters occupy nest cavities that are created by other birds or through forces such as decay or erosion. Most cavity adopters throughout the world nest usually in tree holes or rock niches. Some birds rely on other species and nest in adopted tree cavities, usually woodpeckers, to create their holes. Most artificial nest boxes set out by humans are intended for species like cavity-adopting species that typically nest in old woodpecker cavities. Australia has a significantly high proportion of cavity adopters even though there are no woodpeckers found; the Eucalyptus trees that are found more in the Australian landscape have natural cavities through fungal activity on scars resulting from fallen limbs. All nuthatches are cavity adopters, and many nuthatch species use soil to narrow the entrance of the hole in a tree branch or under a flap of tree bark. True to their name, Rock Nuthatches, and some Persian Nuthatch, nest in rock faces rather than trees. As additional protection, these nuthatches create a large mud nest within the rock cavity. Many other birds also use mud to alter adopted cavities, and mostly they design the entrance so the parents may enter and exit with ease. In most hornbill species of Asia and Africa, females use feces and mud to seal themselves inside a nest cavity and remain there for months. The male is just responsible for providing food to the female and their nestlings through a small slit in the wall made of mud in the cavity opening.

Some unusual nest

Some unusual birds even build nests that do not fall within a single category of nest type. For example, the Rufous Hornero from South America builds a cup nest with grasses enclosed within a hardened mud snail-shaped sphere, complete with separate chambers and entrances.

Nest lining

Most, bird nests are lined with materials unlike those used in constructing the outer structure. Birds use many kinds of materials to line their nests. A bowl of sticks is usually used with softer materials, such as dried grass, mammal hair, or plant fibers. A tree cavity may contain feathers, bark strips, moss, or fur covering the bottom. The primary function of most nest linings is to help in insulating the nest and its living contents and also prevent chicks from getting entrapped in the coarser outer nest materials. Many species line their nests with mixed combinations of natural materials.

Many birds also use feathers as lining material for their nests. Most female waterfowl line their nests with down feathers plucked from their own breasts, but several songbird species line their nests with feathers that are not their own. A variety of species, ranging from starlings to raptors, adorn or line their nests with green plant material. Early biologists, failing to see a function for this “decoration,” wondered if these birds simply might be expressing an aesthetic sense.