Birds are very efficiently adapted to their environment, and most of the characteristics of a bird can be related to some behavioral trait.

Always pay attention to the habits and to the placement of birds; watch for patterns; notice the vegetation both the plant species and their structure. Soon you will notice much more subtle differences and develop a “feeling” about what you might see at each place or where to look for a certain species.

Regional differences in behavior are common. A specific set of conditions or type of food can cause the birds to engage in slightly different behavior. By studying birds in your own area you can observe tendencies that may be unique to the local conditions. These clues cannot be used as reliably in other areas, however. For example, experienced hawk-watchers develop a set of subtle, even subconscious, clues that they use to identify hawks at their home watching point. Traveling to an unfamiliar hawk- watching spot, these same observers can be totally bewildered by slightly different flight styles, different flight lines, and different angles of view or lighting. Researchers who study wild bird populations often amass large databases on these types of individual differences because even subtle variations can be critical components of a bird’s ability to survive or reproduce.

How much does the environment affect bird behavior?

At least some of this individual variation must be inheritable so that it can be passed down to future generations of birds. Only some of the differences among individuals are inherited because some variation is generated by environmental conditions or by various experiences during a bird’s lifetime. This dichotomy often is termed “nature versus nurture,” with “nature” being inherited variation and “nurture” being the variation caused by the environment.

This distinction is important because the environment can have a substantial impact on an individual’s development and overall survival.

Although some of the characteristics measured in wild birds are affected by the bird’s environment, many traits have high heritability. Studies of wild birds show that genetics often accounts for 50–90% of the variation in morphological features such as bill size, wing length, and adult body weight; that is, much of the variation in those traits is passed down from parent to offspring.

Is every bird unique?

Reproduction in birds requires that a female mate with a male. In some birds, the fathers contribute little more to their offspring than their sperm, but this is a basic genetic contribution. The offspring inherit half of each parent’s total genetic material; because each chick gets a different mix of its parents’ DNA, each one is genetically unique, just like most human siblings.

There are two exceptions to these rules, but both are very rare.

Seasonal Changes in Behavior

Another element that keeps bird-watching constantly surprising and exciting is the changing seasonal patterns of distribution and behavior. Birds that are conspicuous and common one month can be scarce and elusive the next. Migratory species can be absent one day and common the next. Understanding the seasonal cycles of the birds’ lives increases our appreciation of the challenges they face and may give us clues to a bird’s identity.

You can expect to see different things each week throughout the year. What you are seeing now may not happen again until this same date next year. Even ancient observers noticed these cycles. This can be one of the most satisfying aspects of bird study because it heightens and confirms our own sense of the grand seasonal changes that happen all around us.

How to identify bird species based on bahaviour?

You can expect birds in natural settings to show similarly set preferences. Many behavioral traits allow you to place a bird quickly into a family or a group of species. For example, a small yellow bird that sits on a conspicuous twig for two minutes looking around is almost certainly a goldfinch and not a warbler. A small yellow bird that flits nervously through the vegetation, not sitting still for more than a few seconds at a time, is almost certainly a warbler and not a goldfinch. Woodcocks, snipes, and dowitchers, even though they are similar in shape and general habits, can always be distinguished by their habits and habitat choices. Robins flying onto a lawn swoop to a landing and hop two or three times before stopping; starlings fly down and land heavily, “sticking” to the ground.

More detailed observations reveal differences that can be useful in distinguishing species. Among the medium-size terns there are differences in the way each species normally dives into the water for fish. Black- chinned and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (and other hummingbird species) hold and move their tails differently when hovering. Different species of dabbling ducks (genus Anas) tend to feed in characteristic ways. These differences are always tendencies, not reliable on their own to identify a species, but they can provide useful clues, even at tremendous distance.

Classification of bird behaviour:

The life of a bird centers on two or three main annual activities: breeding (from courtship to raising young), molt, and in many species, migration. In general, these activities all require a large investment of time and energy, so they do not overlap to any large extent. The winter season is also a challenging time for many species, particularly those that spend it in cold climates, and surviving the winter has a powerful impact on behavior in these species.

Migratory behaviour:

If you learn what behavior to expect at each time of year you will have a basis for some expectations of where birds can be seen at a particular time and what they might be doing.

Throughout the United States and Canada, for example, the identification of spotted thrushes of the genus Catharus is simplified from November through March by the fact that only the Hermit Thrush normally winters here; all other species are far to the south during those months.

Feeding behaviors and habitats

Feeding behaviors and habitats also change; for example, many species of songbirds switch from a diet of mainly insects in summer to seeds or berries in winter and choose correspondingly different habitats.

To find a Palm Warbler in Maine in June you would look in a spruce bog; to find one there in October you would look in a weedy field or in coastal dunes.

To see a Common Snipe in the fall or winter you would search the edges of muddy pools near standing grass and weeds; on the summer breeding grounds you can often find one perched on top of a fence post or spruce tree, giving its territorial call.

Breeding behaviour:

Do twin birds exist?

Twin birds, which develop within the same egg, have been reported from a broad range of bird species. Although twin embryos almost always die before the egg hatches, two chicks have hatched successfully from the same egg on occasion. Only one such case, a pair of captive hatchlings that emerged from one unusually large egg on an Emu farm in New Zealand, has been investigated genetically; test results

revealed that the birds were identical rather than fraternal twins. Both Emu twins survived and grew, although initially, they were smaller than typical chicks of the same age.

Birds without sperm

On a few extremely rare occasions, female birds have reproduced via parthenogenesis without any sperm from a male at all. Parthenogenetic development occurs regularly in a few breeds of domestic turkeys and chickens, and it has been documented rarely in captive Zebra Finches and Rosy‐faced Lovebirds. Surviving offspring in all these cases inherit a subset of their mother’s total genetic variation, but they are not her exact clones; in fact, these offspring usually are male. No case of avian parthenogenesis has yet been documented in the wild.

Reproductive success:

Individual birds within a population differ in their ability to produce viable offspring. In evolutionary terms, this reproductive disparity among individuals is the most direct measure of their variation in lifetime fitness. For logistical reasons, it often is extremely difficult to track the reproductive success of an individual wild bird throughout its entire lifetime. Ornithologists, therefore, often measure fitness in units of “successful nests” or “number of chicks fledged” in one or several years. Nonetheless, a better way to measure fitness is to track how many of an adult’s total offspring survive to reproduce as adults themselves. This is the most accurate index of this original parent’s direct genetic contribution to future generations.

Foraging

One of a bird’s most important tasks is foraging. Much of the anatomical structure of the bird is related to finding and procuring food, and foraging behavior is intimately related to structure. Thus the different wing shapes of hawks and bill shapes of sandpipers, among many other examples, are linked to differences in food and foraging behavior, and because of these differences each species typically behaves in certain ways.

When you watch a bird feeder you will notice that each species uses certain foods and in certain ways. Chickadees choose sunflower seeds, flying in to grab a seed and then flying away. Goldfinches choose thistle seed, perching quietly and nibbling for minutes on end. Sparrows choose millet and hop around on the ground scratching or searching for food.

There are 10,000 bird species living in the world, and more than 10,000 ways for those species to adapt to live. So it’s not often that you find a trait which is truly universal in every single bird species.

But they do exist. Let’s learn some truly universal traits in birds.

Every bird in the world is bipedal, meaning it walks on two legs.

At a very basic level, all birds are endothermic, generating their body heat, and homeothermic, maintaining a consistent body temperature.

Birds are famous for this, all birds lay eggs with hard shells.

All birds are vertebrates meaning they have a backbone.

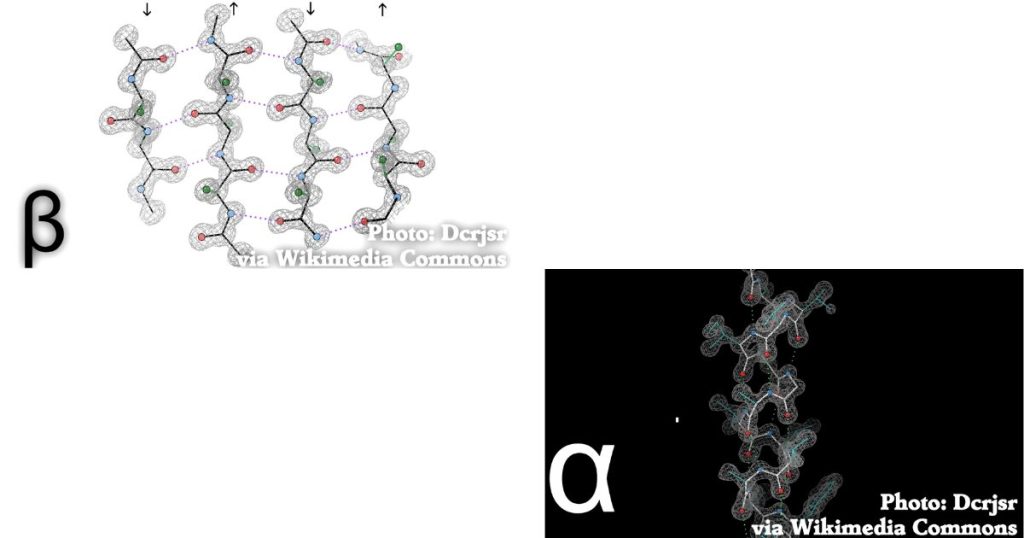

All birds have feathers. These soft fluffy keratin covers are truly universal among birds.

All birds have toothless beaked jaws.

All birds produce beta keratin in their feathers, talons, beaks, and anywhere else that keratin goes. Beta keratin is tougher than the alpha keratin used by mammals.

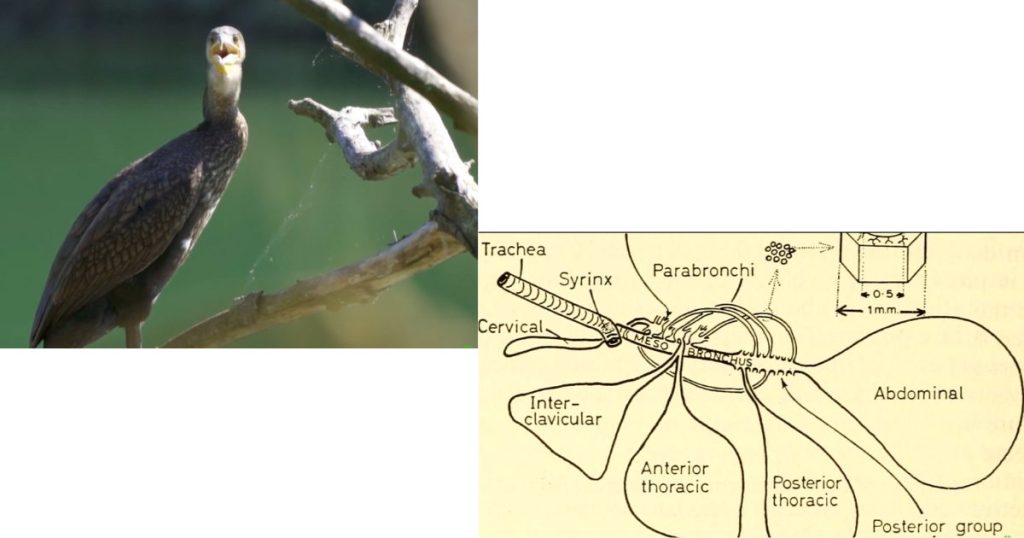

Bird lungs are very, very, very complex, and they are universal in birds.

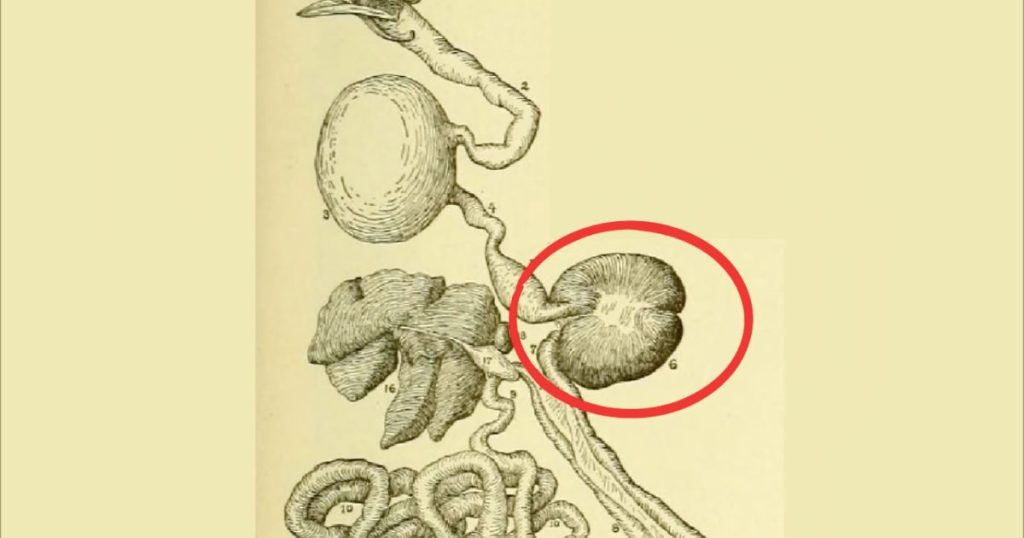

All birds have a gizzard. They use a fleshy bag in their bodies to physically squish food and make it easier to digest. It’s like chewing.

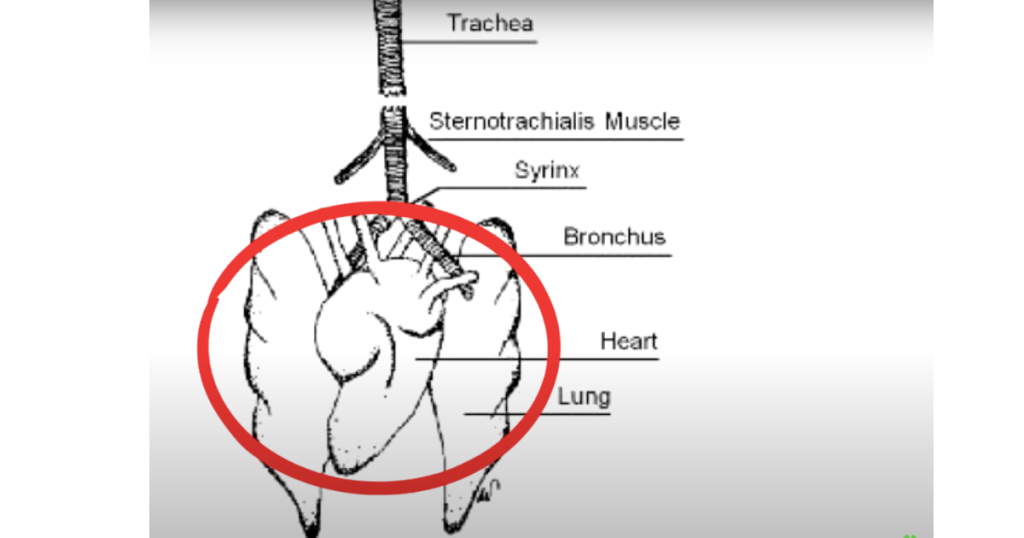

All birds have a four-chambered heart compared to some reptiles, which have three.

All birds have a bone in their eyes, the sclerotic ring surrounding their pupil. This gives them voluntary control over their iris muscles.

All birds have a bony septum in the middle of their heads, separating their eyes.

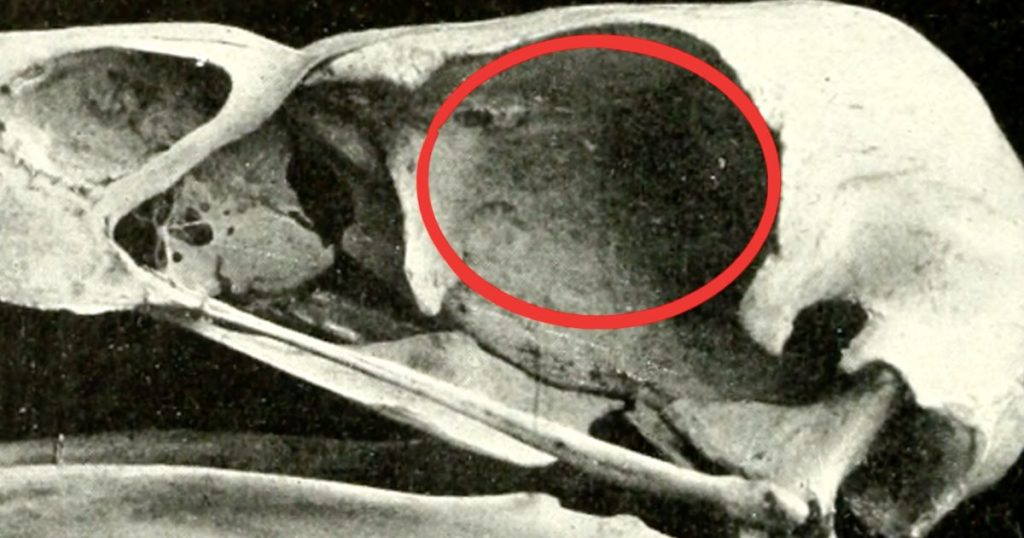

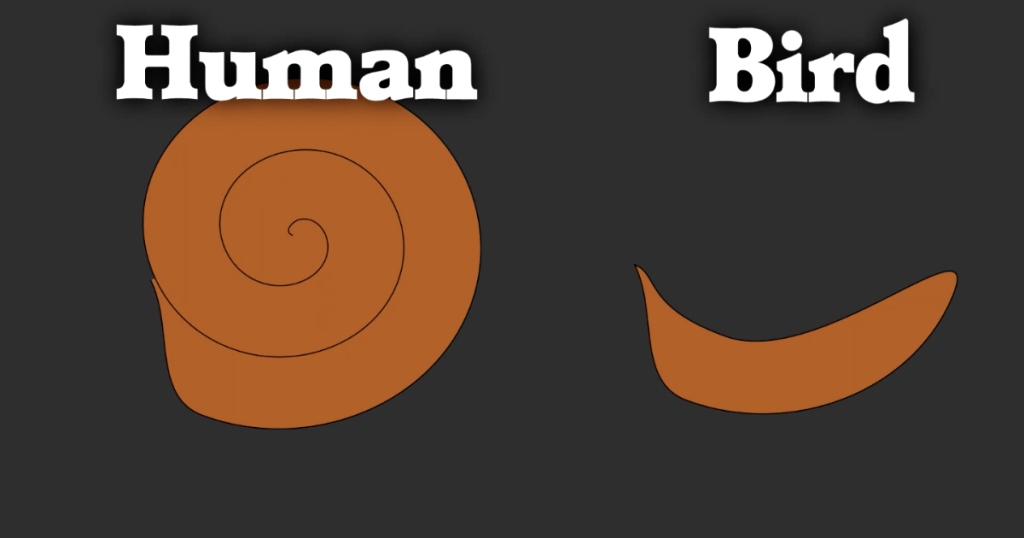

Inside their ears, all birds have a flat cochlea. Not a spiral like we do.

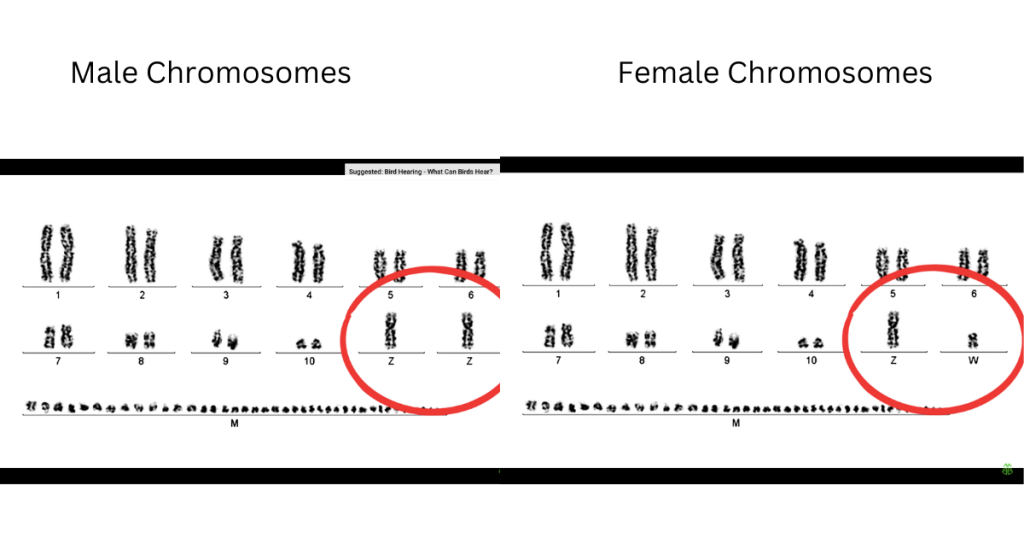

All birds use the ZZ ZW sex chromosome system, where if they have two chromosomes that are the same, they are biologically male, and if they have two that are different, they are biologically female.

Here are some things which are almost but not quite universal but specific in some species birds.

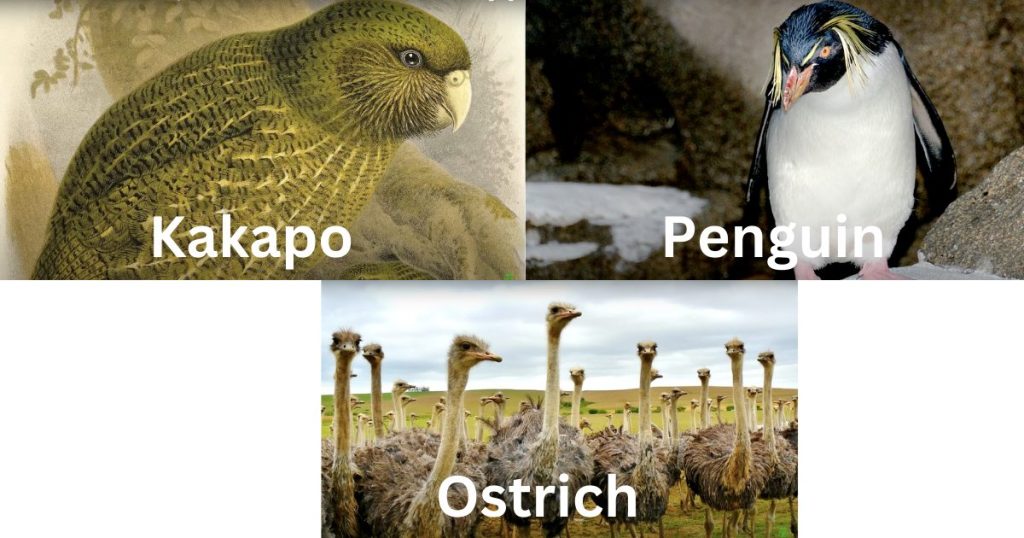

Flight:

Exceptions: Kakapo, Penguin, Ostrich, and other birds.

Hollow bones:

Exceptions: Penguins and Loons.

High metabolic rate:

Exception: Dusky Munia.

Good vision:

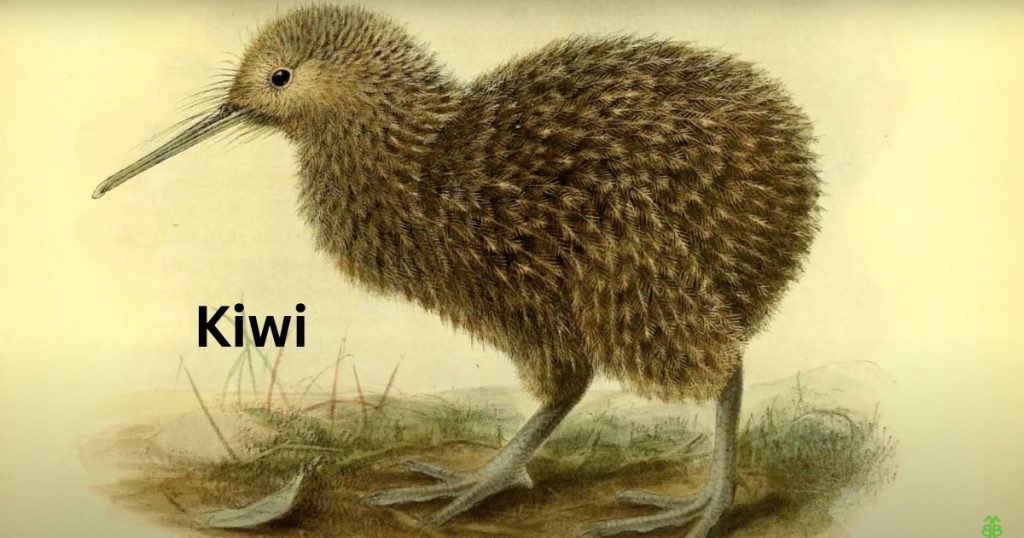

Exception: Kiwi

Poorly developed sense of smell:

Exception: also, the kiwi

Single ovary:

Exception: the kiwi again!

Wings:

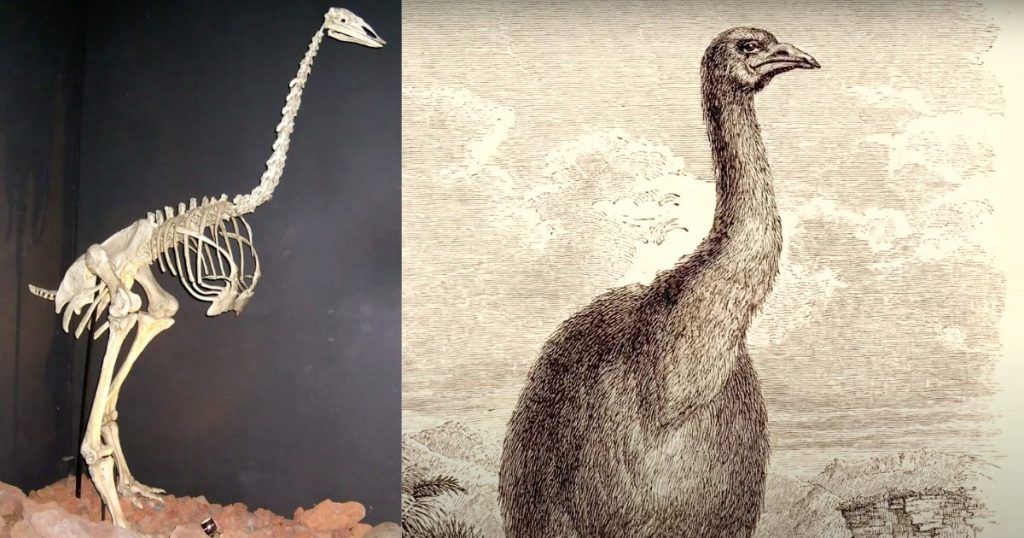

Exception: Moa and Elephant Bird, both of which are extinct. Probably because they didn’t have wings, but they did go extinct within human history.

Uric acid production:

That white part in bird droppings?

Universal in birds except for hummingbirds which can produce ammonia.

An all-purpose cloaca:

A single opening for both feces and urine.

Exception: Ostrich

Birds their habits and features:

Birds and their Food:

Birds eat many different types of food. For example, some eat insects, some eat fish, some eat meat, some eat seeds, and some eat fruit or nectar.

Birds and Feathers:

All birds have feathers, similar to our hair and fingernails, feathers consist of keratin, feathers help birds maintain warmth, helping them to fly, climb up and down trees,

and serve as an adornment or as a disguise,

the flight feathers on arms are like the wings of an airplane and the tail feathers are like to the rudder of a ship.

Birds and Flying:

Most birds fly, but not all of them. Some birds, like penguins, use their wings to help them swim instead.

Other birds, like the ostrich, don’t need to fly because they can run fast. Still others, like the kiwi, were able to do without flight because the islands on which they live have few native predators.

Birds and Wings:

All birds have wings; ostriches are ratite. They can run fast but cannot fly. They’re too heavy for that. Penguins can neither fly nor walk, but they’re very good swimmers. The Gentoo is five times faster

underwater than the crawling world champion. He can swim as fast as 22 miles an hour, and some birds are good at climbing. The woodpecker not only uses its claws for climbing but also uses its tail feathers and bill.

Birds and Bills:

All birds have bills. Like the feathers, the bill has keratin. Bills not only serve for chewing, but as a gripping tool to bite things into, filter water, and drink. There are many different kinds of bills that look similar to a cooking spoon, like a rhino horn, a shoe, or drinking straws.

Among all birds, the Australian pelican has the longest bill. It can measure 20 inches in length.

Bird’s body temperature:

Birds are warm-blooded. But, two bird species can reduce their body temperature. One of them is the hummingbird, which always needs energy but can’t eat at night; So, it reduces its body temperature and enters a kind of nighttime torpor. The common poorwill also hibernates for several weeks at a lower temperature.

Birds and Colors:

Birds are one of the most colorful animals on the planet. While many birds have brown, gray, black, or white feathers, colors that help camouflage them and hide them from sight, other birds put on beautiful displays. In many cases, when we see a brightly colored bird, it is the male. Females are often more quiet colors which makes them harder to spot. The male birds wear their bright, bold feathers to show the females how strong and healthy they are, so the females know they would make good fathers.

To know more about birds and colors click here

Birds and Eggs:

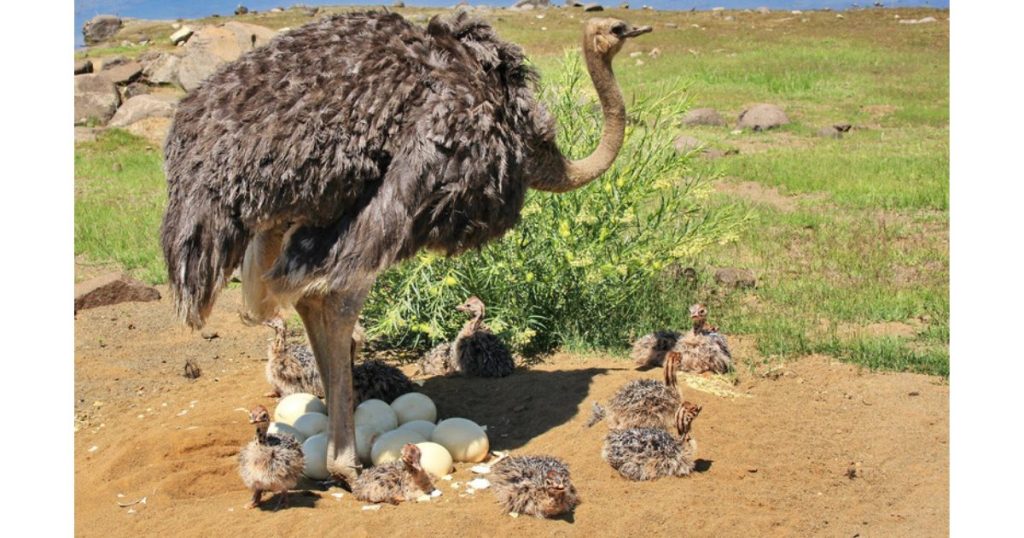

All birds lay eggs. Hummingbirds lay the smallest egg.

The egg of the bee hummingbird is about 0.2 inches long. Ostriches lay the biggest bird’s eggs. They can weigh up to 5.5 pounds, so hard that an adult human can stand on them without breaking.

Not all eggs are white or brown. The thrush, bullfinch, starling, and blackbirds are bird species that lay blue, and emus lay green eggs, and oyster catchers speckled eggs.

Birds and Incubating eggs:

Once eggs have been laid, someone has to take care of them. In some bird species, both parents keep the eggs warm or incubate them. In others, only one parent does. Once the eggs have been laid, they may take as little as 10 days to hatch or as many as 80.

Birds and their young ones:

When the eggs hatch, the baby birds need help to survive – some more than others. Some baby birds hatch blind and featherless and need to be fed and kept warm by their parents.

Other chicks are ready to run around and eat the same day they hatch out.

There are even a few kinds of birds that can fly and take care of themselves as soon as they hatch!

Other birds, however, will take care of their chicks for a very long time. The greater frigatebird will help feed and take care of its chick for almost two years after it hatches.

There is one more universal characteristic of birds,

which is that every single one is amazing!