Coloration and patterning play important roles in the behavioral ecology of birds. All animals must strike an evolutionary balance between hiding from predators and being conspicuous for social signaling. For many animals, concealment is prioritized over advertising. Thus, just as the earthy, cryptic colors of many mammals, reptiles, and amphibians make them relatively inconspicuous, so too, many birds sport brown, gray, and olive‐green tones that render them harder to see.

On the other hand, many birds are brightly colored, perhaps because flight makes them less vulnerable to predators.

Plumage and birds

Bird’s plumages declare the identity of their species, their age, and status as individuals, advertise their health and are the centerpieces of a lot of sexual selection. The inherent ability of feathers to form complex colors and patterns, when coupled with the social and communicative nature of birds themselves, has made birds some of the most ornate animals on earth.

Predator avoidance

Predation is a significant threat for most birds, and avoiding predation appears to be the main reason so many birds have evolved cryptic coloration. There are numerous ways for a bird to create crypsis or patterning that generally causes an animal to blend in with its background.

Many birds use background matching: their plumages include colors and patterns that mimic the substrates on which they are most often found.

Substrate Examples

The mottled patterns on birds of the scrub or forest floor are excellent examples;

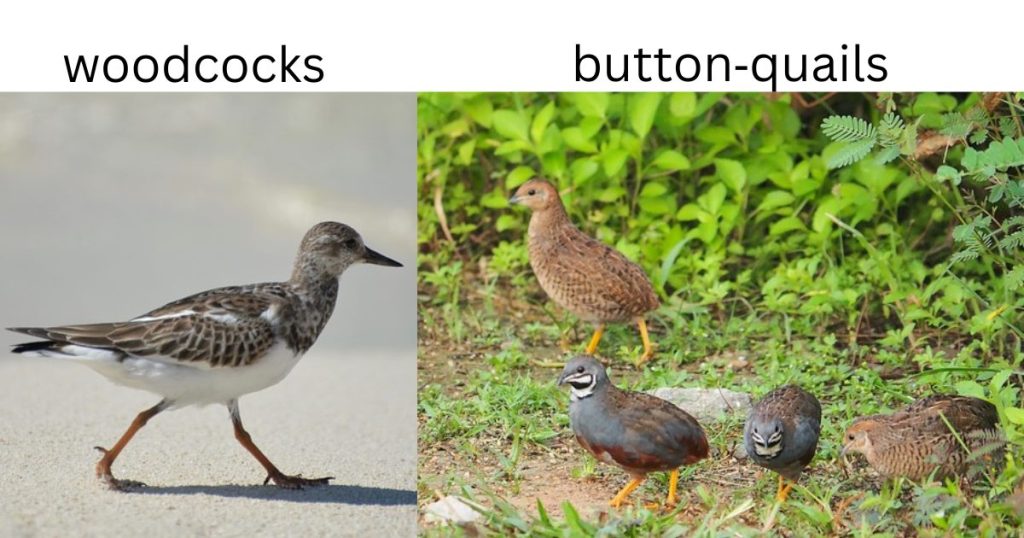

The woodcocks of the northern hemisphere, button‐quails of Australia, and many other birds worldwide resemble the leafy litter in which they are frequently found.

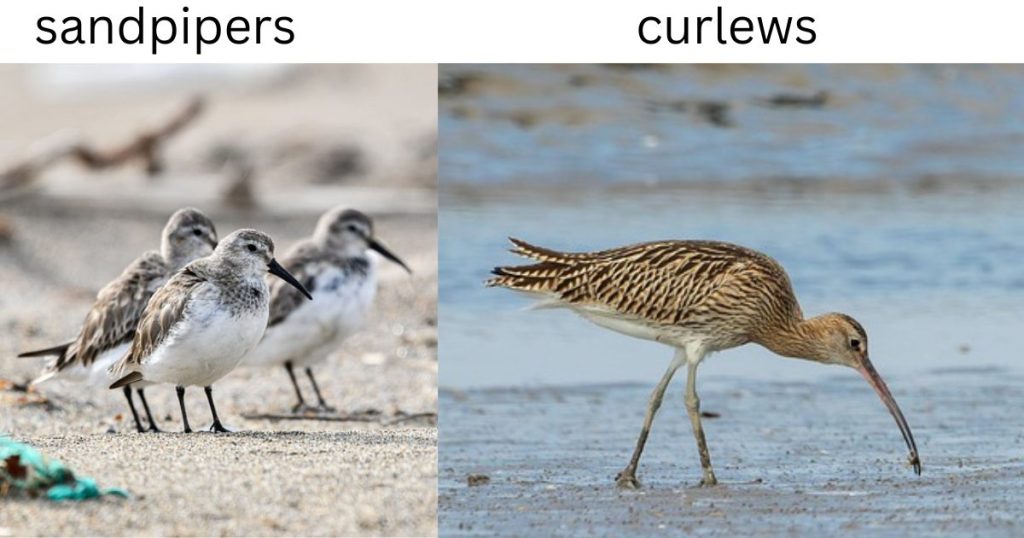

Nearly all shorebirds, from sandpipers to curlews, have mottled brownish backs that conceal these ground nesters during incubation as well as during foraging on beaches, mud flats, or grasses.

Worldwide, birds of grasses and reeds—the bitterns, many Old World warblers and Old World buntings, most New World sparrows, and the cisticolas of Africa often have patterns with many shades of brown arranged in long streaks to help them blend into the stripy vegetation they live within.

The northern‐dwelling ptarmigans molt from their mottled brown summer plumage to a coat of pure white that blends with heavy snow cover in winter;

Similarly, the Snowy Owl (Bubo scandia- cus), Snow Goose (Chen caerulescens), and Snow Bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) of the arctic tundra all wear snow-matching white plumages.

Even birds that look gaudily colored in pictures may blend perfectly into their natural surroundings; many birders visiting the tropics have had the humbling experience of scrutinizing a well‐lit, bright green, and visually “birdless” tree that is nonetheless squawking with birds before finally glimpsing one well-camouflaged leaf green parrot just as the flock of a hundred takes off!

Some birds use disruptive coloration. Like the camouflage of military and hunting gear, disruptive plumage coloration uses larger patches, streaks, or other bold color patterns to break up the outline of the bird, distracting an observer from noticing the whole bird as one form. For example, the bold, black neckbands of many plovers make it more difficult to distinguish the whole bird as one form.

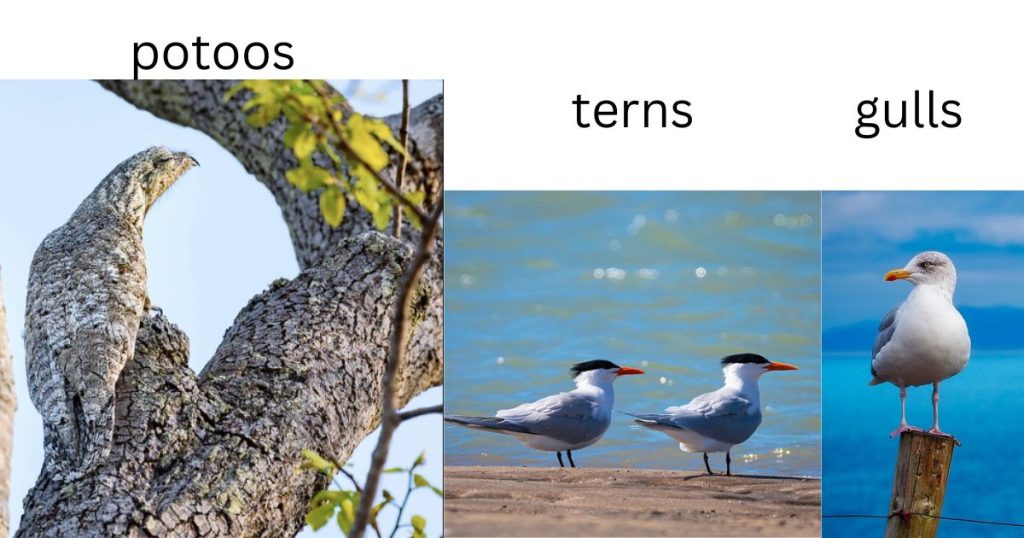

Another strategy to minimize detectability, many birds are hard to see because they are darker on top than below, a pattern known as countershading. Many bird species, including smaller plovers, sandpipers, and songbirds, exhibit this pattern. With the darker backlit by the bright sun overhead and the lighter underparts in the shade of the bird’s own body, the bird appears to be nearly one color, and until it moves, predators have difficulty seeing it as a three‐dimensional object. In addition, white underparts may reflect the color of the ground, producing even more effective camouflage. Countershading is especially widespread in open country birds that are vulnerable to distant predators hunting by sight. It also is common in birds that spend much time on or flying above the water, such as loons, grebes, ducks, auks, gulls, terns, and many pelagic birds.

How birds use cryptic plumage

Birds may further increase the benefits of cryptic plumage by using behaviors that add to their crypsis.

1# Holding still

Simply holding still is a good way to avoid attracting the attention of predators.holding still

By freezing and flattening against the beach, young terns and gulls eliminate their shadows and look just like bumps on the sand.

The nocturnal potoos of the neotropics complement their mottled brown and gray plumage with behavior; they spend most of the day just sitting, often perched on the limb of a dead tree, with neck stretched up and large eyes closed, looking like an extension of the limb.

Many small owls adopt similar stick postures. The strategy of remaining relatively still also works for many predators, such as herons prospecting for fish or frogs along a shoreline. In some contrasting cases, subtle movement can actually enhance concealment. For example, bitterns that accentuate their streaked pattern by standing in a marsh with their beaks pointed skyward will sway slightly from side to side with the surrounding reeds as the wind blows.

2# Conspicuous tail or wing

In a creative twist regarding the use of behavior to enhance concealing plumage, many birds have conspicuous tail or wing markings that draw attention only once the bird flies off. The barred black and tan upper parts of the New World flickers, and the black and white upper parts of the Eurasian Hoopoe (Upupa epops) are easily overlooked against the ground on which they forage. Yet in flight, the bright yellow wings and white rump of the flicker and the bold, black‐and‐white wing pattern of the Eurasian Hoopoe are visually striking. When such attention-grabbing plumage patterns are revealed suddenly, they may startle an approaching predator.

3# Distracting tail tip

Similarly, many passerines have distracting contrasting (usually white) outer tail feathers or feather tips that may cause a predator to hesitate or strike the bird’s tail and miss the primary target of its body. Because these conspicuous markings can be made to disappear when the bird lands, suddenly concealing the bird’s position, they may further confuse predators that had focused primarily on the bold markings during the pursuit.

4# Poisonous feathers

Predation avoidance via feathers is not restricted to their appearance: at least one group of birds sequesters toxins in its feathers that make them distasteful and potentially even poisonous to predators.

One final note on predation and avian coloration:

Different predators have different visual capabilities, so one cannot assume that all prey appears as conspicuous or as cryptic to predators as they do to humans.

For instance, most mammalian predators and nocturnal avian predators (such as owls) lack color vision. Many bright yellow or red birds thus may be relatively inconspicuous to these predators, which see the colors as shades of gray.

On the other hand, hawks, eagles, and other avian predators that are active by day generally have full-color vision, including some UV wavelengths. Thus, markings on a bird may be cryptic for one kind of predator but not for another.

Do birds change their color:

In some male birds, after their autumn molt, the colors are far less vibrant from new feathers. The bright colors are hidden. The Brambling, a winter visitor to the UK, is a good example of this,

when it arrives here in the autumn, the male’s head and back have a mottled Brownish appearance,

yet by the time, it leaves in late winter, its head and back have been transformed into a striking solid black color,

they achieve this by what is termed abrasion.

Whereby the end of the feathers are slowly over time worn away by the

the action of flying, exposing the bright-colored feathers underneath.

House Sparrows:

You could see this happening if you got house sparrows in the garden. After the autumn molts, the dull fringes almost obscure the black tip on its feathers in male birds

Gradually, over the winter, due to wear and tear, the end of the feathers is worn away, giving the bib a muddled appearance that will have slowly disappeared by the spring.

Benefits of doing this:

This clever adaptation means it can go through the winter period with more subdued plumage, making them less visually obvious to a predator. And yet, by the breeding season, they will acquire their vibrant appearance to attract a female without having to go through the arduous task of molding again.

Some other birds do this:

The reed bunt is another bird that uses this technique and, by spring, changes dull, mottled head for a striking black and white appearance.

The starling is another bird that uses this abrasion technique to tone down its colors after it throws to mold and yet effortlessly regain them again by the following spring.

The one shown here, only halfway through its mold, is a first winter bird; as you can see, it still has its juvenile coloring on its head. Not only do they require white tips to the head and body feathers, but they also have black bills and brown legs, all of which combine to give a duller appearance and make them less vulnerable to predators during the winter. By late winter, the yellow coloring of the bill is returning, and the legs are now pink. The white tips of the feathers steadily wore away, and by the spring, the head and breast will have regained their luminous black appearance with a Norvin green Sheen that glistens in the sunlight. This first winter young bird will keep its gray-brown coloring until it gets its first adult plumage after the autumn mold.

There is an incredible variety of colors in birds. Lets see some awesome birds,

Red:

It’s amazing to see a bright flash of red against the green of a leafy tree.

Red feathers are poor camouflage, but they offer birds a chance to stand out for their courtship or territorial displays. Also, there is a theory that the bright reds of social birds like parrots help the flock keep together. But whatever the reason, we can appreciate these bold red birds.

Pink:

There are different shades of pink feathers,

but almost all pink pigment comes from plant sources. Sometimes pink birds eat plants directly, but it’s more common to eat bugs or shrimp containing plant nutrients. Then as each feather grows, the bird puts in some beautiful pink pigment.

Orange:

Orange feathers have two main ways to appear orange.

There are plant-derived pigments that make vivid orange, but the bird has to get them from its diet.

Or there are melanin-based oranges,

which are less intense but can be made at any time. But both make it possible to appreciate orange birds.

Yellow:

Yellow is a flashy color. But these birds are not trying to hide.

They are trying to be seen!

Probably by other members of their species, for courtship, or for defending territory. Yellow is also a happy color because seeing a bright yellow bird will surely make our days more cheerful.

Green:

Green is an amazing camouflage color.

Green birds almost disappear when they fly up into green leaves.

So it’s no surprise that many, many birds are green. But, the surprise is that almost no bird produces green pigment. Almost every green feather is structurally blue with a layer of yellow pigment.

Blue:

Every single blue feather in the world appears blue due to its shape.

No exceptions.

In many birds, there is a thin layer of air bubbles in the protein surface of the feather. The bubbles are just the right distance apart to bounce out blue light. But the feather itself is either dark grey or clear.

In birds that have shiny blue feathers,

it’s because of thin, transparent films. But there is no such color as a blue pigment in birds.

Purple:

Purple is surprisingly rare in birds and is usually found in small patches of purple feathers. But it’s still such an eye-catching color to see!

It’s important to remember that most birds can see ultraviolet, so there may be some beautiful deep purple birds that our eyes can’t detect.

Black:

Black is a fairly common color in birds, excellent for camouflage and matching every other color of feathers.

It looks dull in diffuse light, but at the right angle, black feathers show off the amazing detail of individual feather shapes. And it also allows us to appreciate the wildly different forms that bird bodies have!

Grey and black both come from melanin.

Melanin and Albinism in birds:

Lots of melanin makes a black feather, and less melanin makes all the varieties of grey.

The steps to make melanin are common in animals, but a single mutation can shut it down and stop melanin production entirely, so anytime you see a gray or blackbird, it’s one mutation away from being the same shape and size but with pure white feather is called Albinism.

Brown:

Brown is the best camouflage color for almost every situation. It blends with dirt, mud, rocks, bark, and branches.

It’s used by predators and prey alike because not being seen is almost always good. It’s the most common bird color in the world. So there are lots of interesting birds to choose from!

White:

It’s not common knowledge, but white is a structural color based on the feather’s shape.

The clear keratin proteins of the feather include air channels that bounce out all types of light equally. Therefore, if a white feather is soaked in a liquid of just the right properties, the liquid will fill all those channels and clear the white feather!

All Colors:

It’s rare for a bird to be all one color. Instead, most birds have patches of different hues and brightness. But some birds take this to the extreme and are covered in patches of vibrant, striking color.

We today learned about colors in birds!

Thanks for taking the time to learn about the rainbow of birds!